Charity and Funder

Relationships: Unlocking the

Potential

By

Thomas W Keenan

(Master of Business Administration)

Thesis

Submitted to Flinders University

for the degree of

Doctor of Philosophy

College of Education, Psychology & Social Work

19

th

November 2021

i

Abstract

The Australian charity sector is extensive and operates across most aspects of our society. It

provides a diverse and frequently complex range of services and delivers essential support for

individuals, families and communities. The size, reach and scope of the sector means that any

improvements to the effectiveness or efficiency of charities would likely lead to wide-ranging and

far-reaching benefits to the whole of Australian society and beyond. Consequently, this research

investigates, interrogates and reports on the impact the current model of charity funding has on their

effectiveness and efficiency. This research also investigates the nature of the relationship between

charities and funders. A mixed method approach was used in this research.

The theoretical framework for this research is a blend of Phenomenology and Resource

Dependency Theory (RDT). The former was adopted as a means of exploring ontological

understandings and taken for granted meanings of the charity and funder relationship in rich and

nuanced ways. RDT with its considerations of dependency and relational power was used to

undertake a detailed exploration into how the organisational effectiveness and efficiency of

Australian charities are being impacted by the current model of funding and how this model is

influenced by the power dynamics within the charity/funder relationship.

This research has found that the organisational effectiveness and efficiency of charities is being

significantly compromised by how they are funded. This is primarily due to the fractured

charity/funder relationship, which is skewed, very much, in favour of funders. Funders hold all the

power in this relationship; they know it and they exploit it. This power imbalance presents, most

frequently, in how charity funding is sourced, awarded and then controlled. The mechanisms for

securing funding are inconsistent, subjective and consume a significant amount of charity resources,

all of which dilutes, not inconsiderably, the value of the funds awarded and therefore the impact that

charities can have. e initial award of funding to the dictating of

where and when funds should be used and the refusing of funding requests for capacity building

type funding that would afford charities the opportunity to become more organisationally effective

and efficient. As a result, organisational competence is further compromised. The charity/funder

relationship matters less to funders than it does to charities, as does the impact of the funds

provided, which is of little importance to funders.

ii

Another important finding of this research is that of the reality of being a charity employee. Funders

hold charities and the employees within in low regard. They demonstrate little concern for the well-

being of charity employees or their working conditions. Charity employees are compromised

regarding income, working conditions and job security. The reality is that being a charity employee

is not an attractive proposition.

iii

Contents

Abstract

i

Contents

iii

List of Tables

vii

List of Charts

viii

Acknowledgements

ix

Declaration

x

Chapter 1 - Introduction

Page

1.1

Preamble

1

1.2

Introduction

3

1.3

Framing and scope of the research

7

1.4

Research questions

9

1.5

Definitions

10

1.5.1

Charities

10

1.5.2

Funders and motivation

10

1.5.3

The charity/funder relationship

11

1.5.4

Funding models

11

1.5.5

Organisational effectiveness and efficiency

11

1.6

Background

13

1.7

Reporting and performance

16

1.7.1

Charities

16

1.7.2

Funders

20

1.7.3

Conclusions

26

1.8

Limitations and delimitations

27

1.9

The significance of the study

28

1.10

Structure

29

1.11

Summary

30

Chapter 2 Literature Review

Page

2.1

Introduction

31

2.2

Relationships within and between organisations

32

2.3

The history of charities and charitable giving

33

2.4

The history of charity legislation

37

2.5

The rise of the welfare state

45

iv

2.6

The Beveridge Report

51

2.6.1

54

2.7

Charity funding

61

2.8

Organisational effectiveness and efficiency of charities

77

2.9

The motivations of funders

80

2.9.1

Government funding and the motivations behind it

82

2.10

The charity/funder relationship

86

2.11

What is the gap/opportunity that this research seeks to fulfill?

91

Chapter 3 Methodology

Page

3.1

Introduction

92

3.2

Theoretical Framework

93

3.3

Research approach

100

3.4

Research parameters - What is in scope and what is not?

104

3.5

Data gathering techniques

105

3.5.1

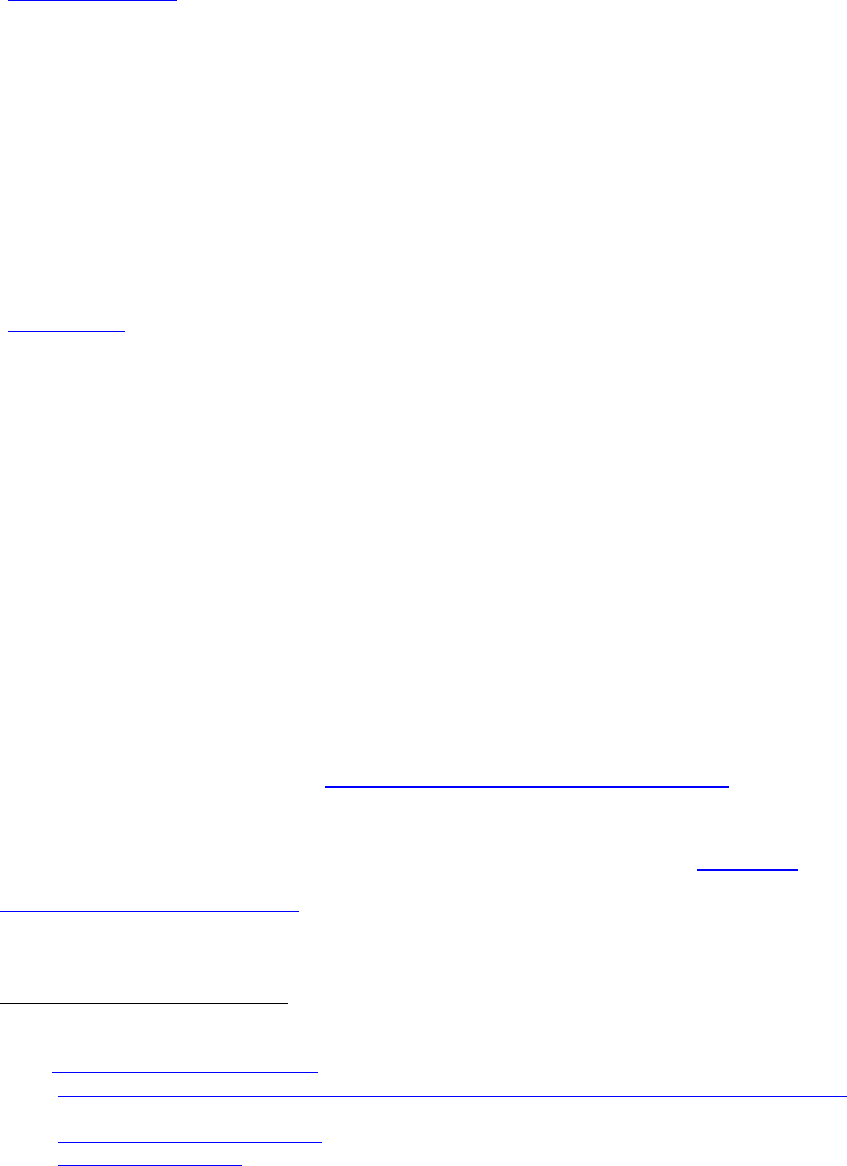

Tranche 1 - Quantitative data gathering & analysis

106

3.5.2

Tranches 2 & 3 - Qualitative data gathering &

analysis

113

3.6

Limitations of the study

117

3.7

Ethical considerations

118

Chapter 4 Findings from the financial survey

4.1

Introduction

119

4.2

Financial survey questions

120

4.3

Outputs and interpretations

121

4.4

Conclusions

131

Chapter 5 Findings from the interviews with charity leaders

Page

5.1

Introduction

132

5.2

Discovering emergent themes

138

5.2.1

The complexities of securing a grant

138

5.2.2

The diminished ability to establish and follow any form

of strategic path

143

v

5.2.3

The inability to invest in programmes or projects that

145

5.2.4

The disproportionate amount of organisational resource

deployed to secure and maintain future funding streams

148

5.2.5

The realities of being a charity employee

150

5.2.6

The partisan nature of government contracts

153

5.2.7

The unwillingness or inability of charities to articulate to

funders the deficiencies of the current funding models

156

5.2.8

158

5.3

Conclusion

161

Chapter 6 - Findings from the Interviews with Funders

Page

6.1

Introduction

163

6.2

Discovering the emergent themes

168

6.2.1

The Australian charity sector

168

6.2.2

Charity performance

171

6.2.3

The charity/funder relationship

174

6.2.4

Funders practices and performance

178

6.2.5

Government

184

6.3

Conclusion

188

Chapter 7 Discussion

7.1

Introduction

191

7.2

Comparing the emergent themes

192

7.2.1

The environment in which funding is awarded

195

7.2.2

Control over the resources awarded

202

7.2.3

Treatment of charity employees

207

7.3

Addressing the research questions

210

7.3.1

Sub-question 1 - How does the funding of charities

currently occur?

210

7.3.2

Sub-question 2 - What is the nature of the

relationship between charities and their funders?

212

7.3.3

Sub-question 3 - What are the motivations of

funders?

214

vi

7.3.4

Main research question - Is the organisational

effectiveness and efficiency of charities impacted

by how they are funded?

216

7.4

Closing commentary

219

Chapter 8 - Conclusion

Page

8.1

Purpose of this research

221

8.2

Summary of the findings

222

8.3

Contribution to knowledge

224

8.4

Further research

226

8.5

Implications for practise

227

8.6

Concluding comments

229

Appendices

Appendix 1

Data Analysis Formulas used and outputs achieved.

Appendix 2

Quotations taken from Interviews with Charity Leaders listed under

Domain Summaries.

Appendix 3

Quotations taken from Interviews with Funders listed under Domain

Summaries.

Appendix 4

Calculations - Charity resource requirements Section 7.2.1.

References

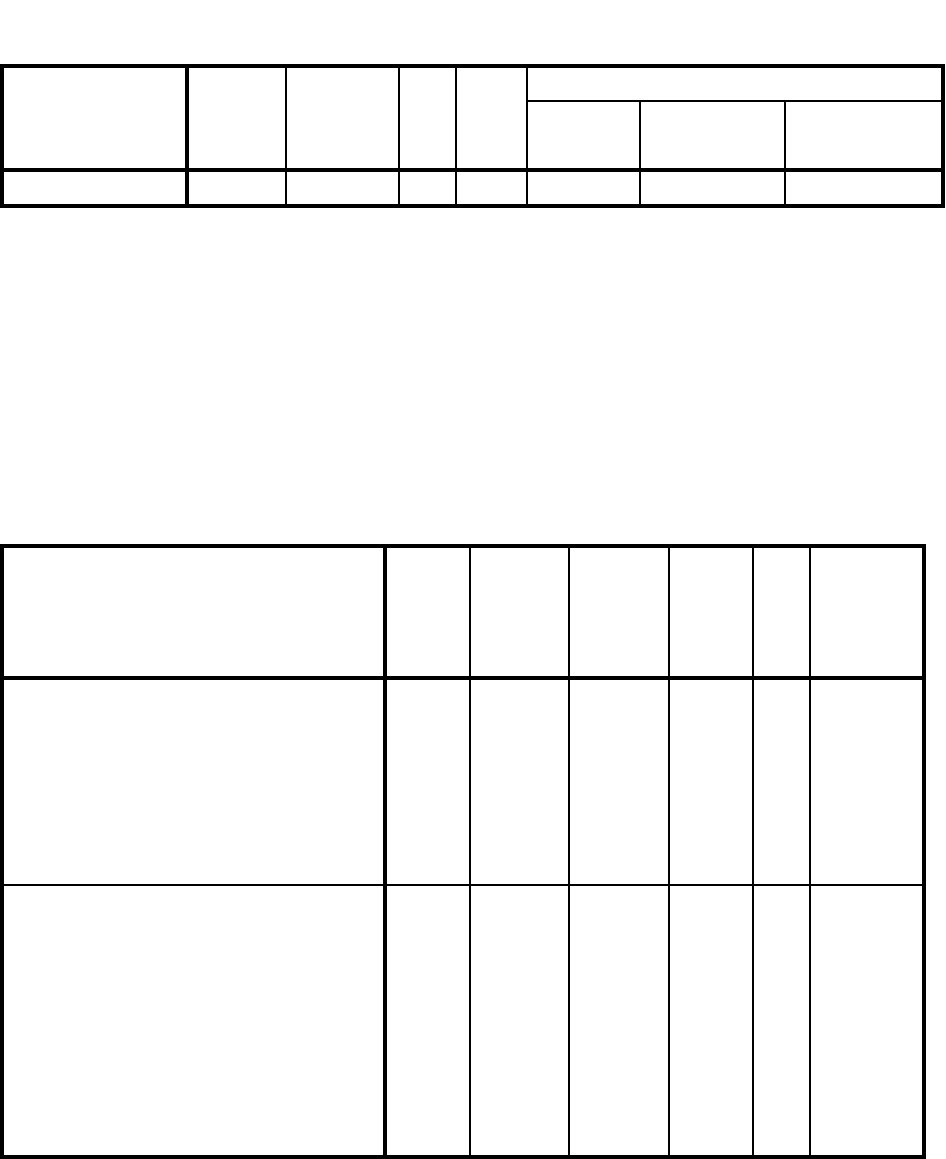

vii

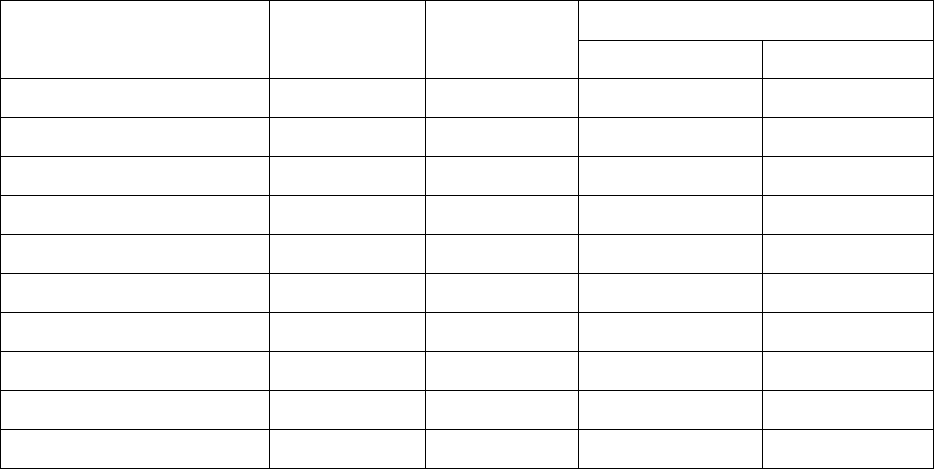

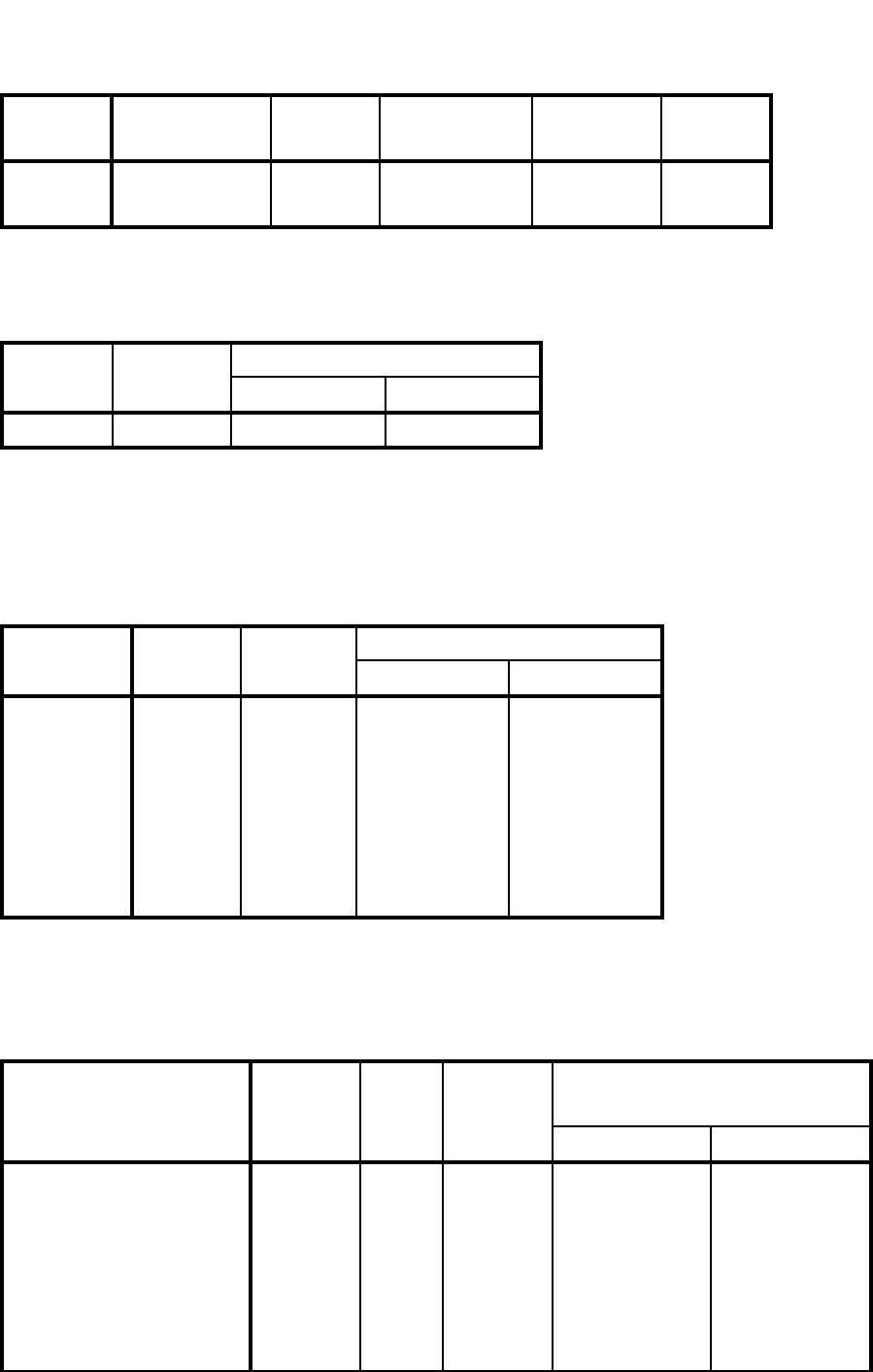

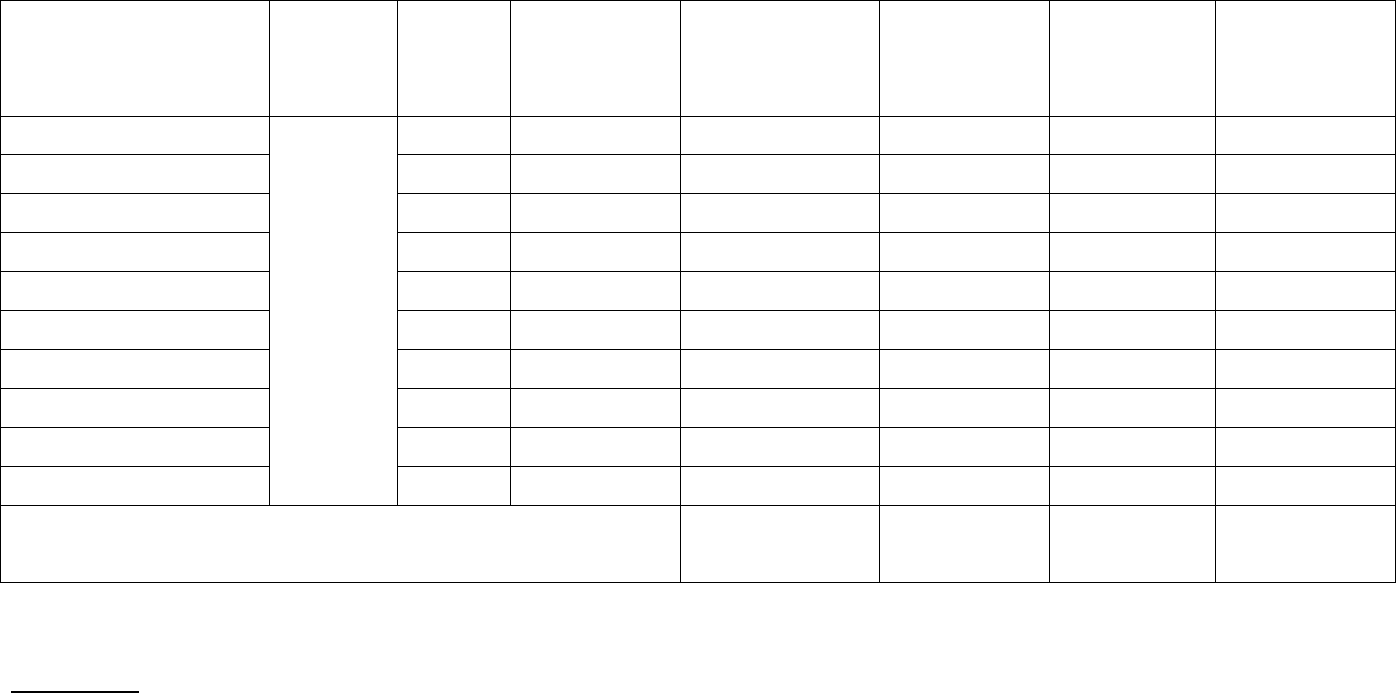

List of Tables

Page

Table 4.1

Annual income & distribution of donations and grants for all charities

surveyed

121

Table 4.2

Income Sources & Contribution to Income of all charities surveyed

122

Table 4.3

Size of Grants/Donations Received & Contribution to Income of all

charities surveyed

125

Table 4.4

Term of Grants/Donations Received & Contribution to Income of all

charities surveyed

129

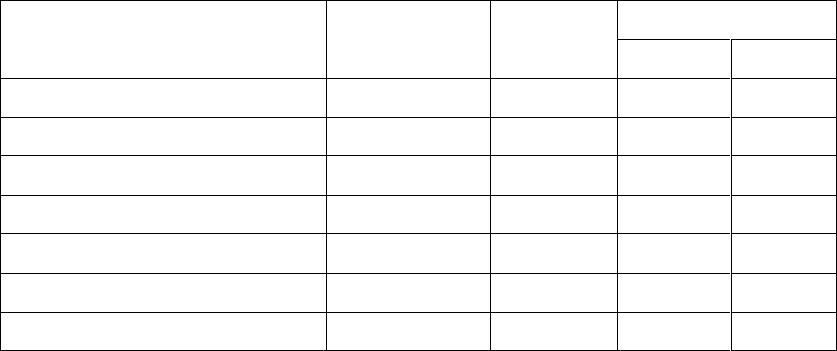

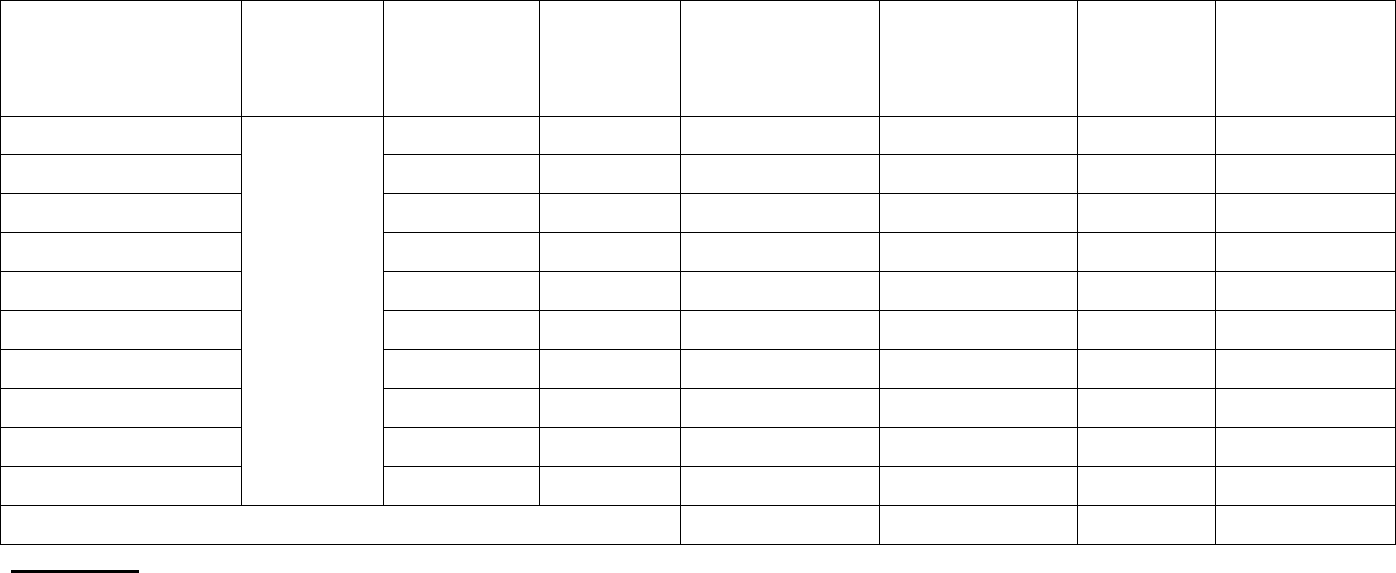

Table 5.1

Profile of charity leaders interviewed

133

Table 5.2

Domain Summaries and Themes Charity Leaders

135

Table 6.1

Profile of funders interviewed

164

Table 6.2

Domain Summaries and Themes - Funders

165

viii

List of Charts

Page

Chart 1.1

Scope of the Research

7

Chart 1.2

Purpose of Australian charities

15

Chart 1.3

Most common beneficiaries of Australian charities

15

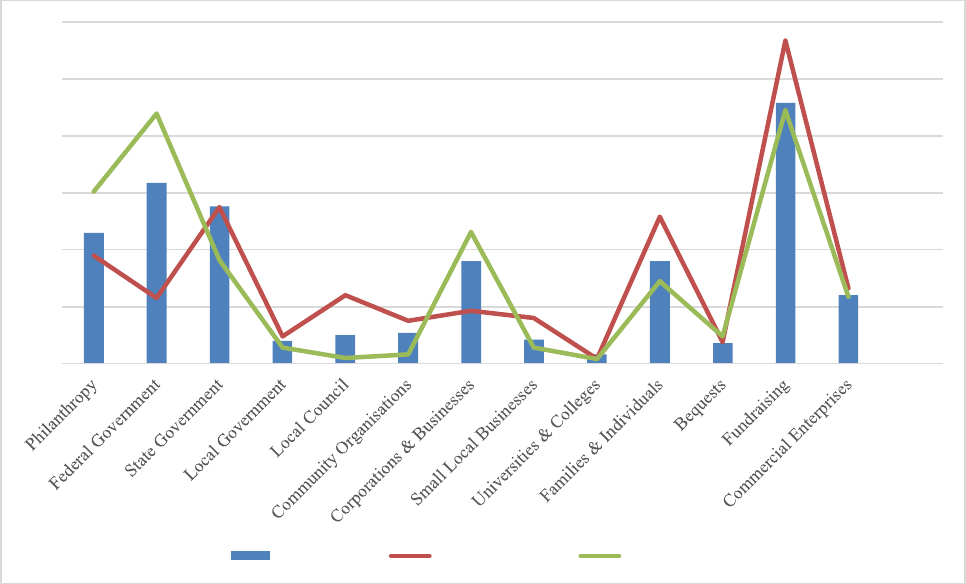

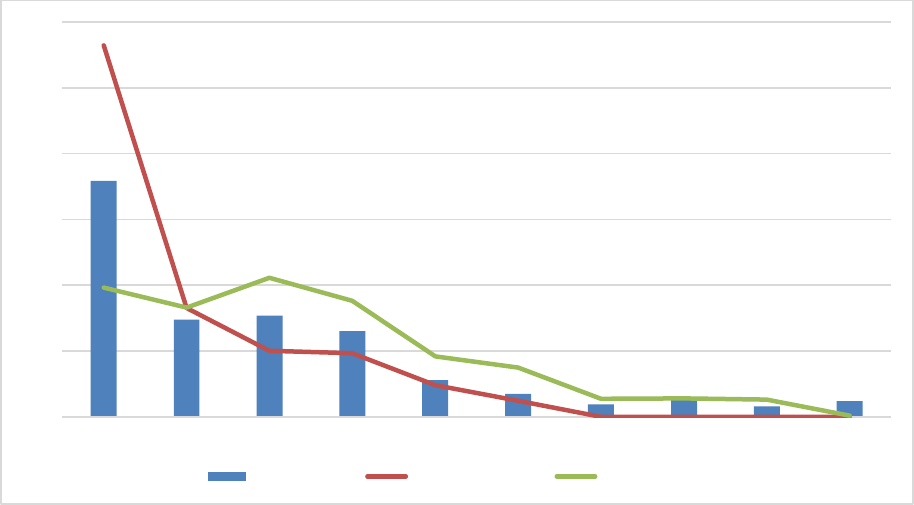

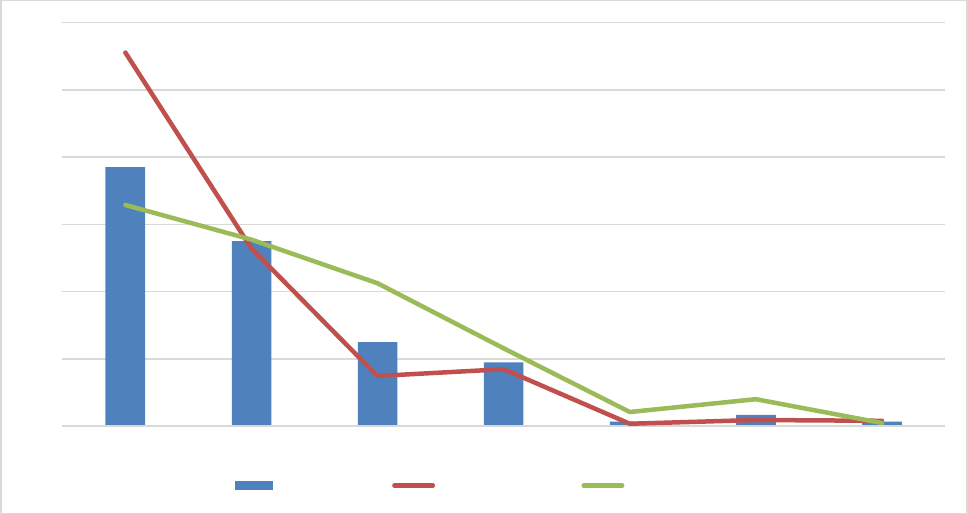

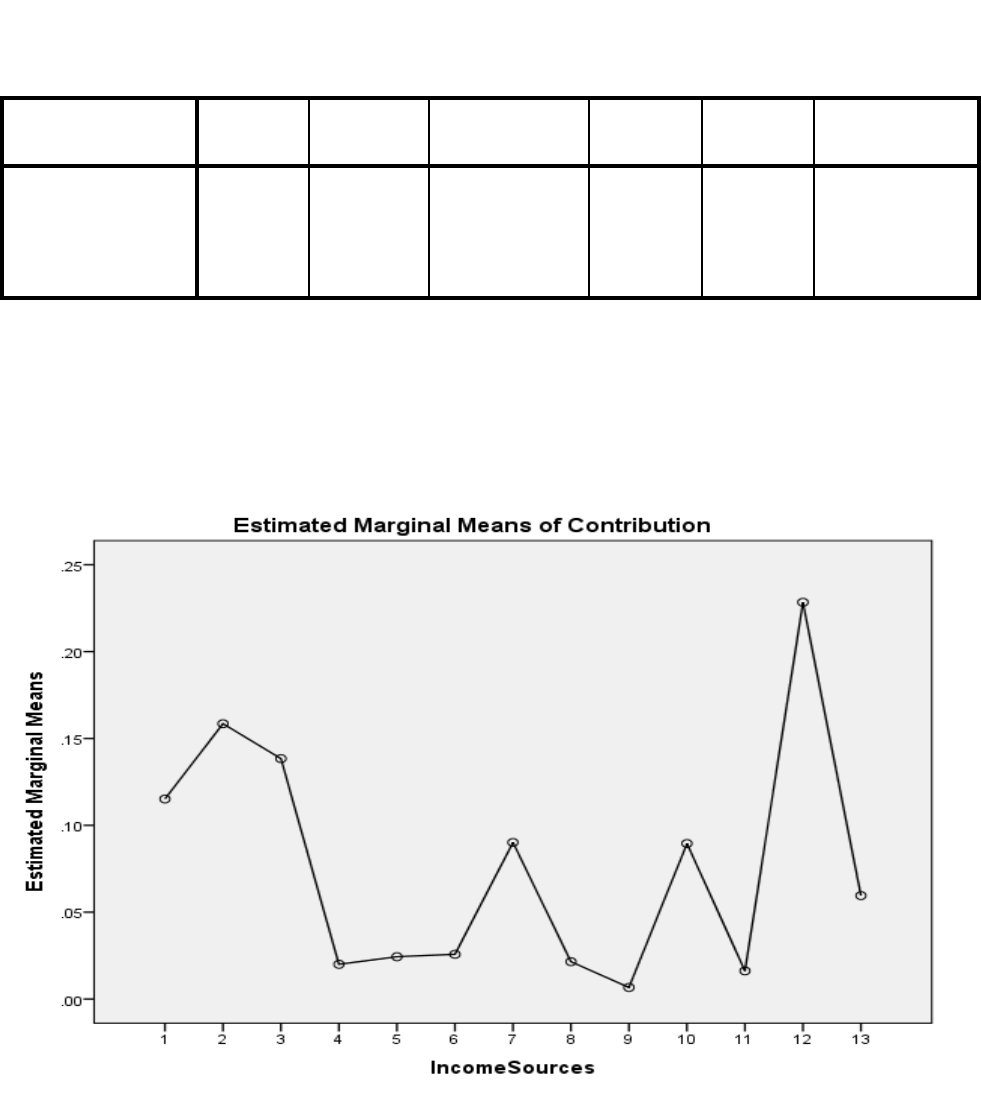

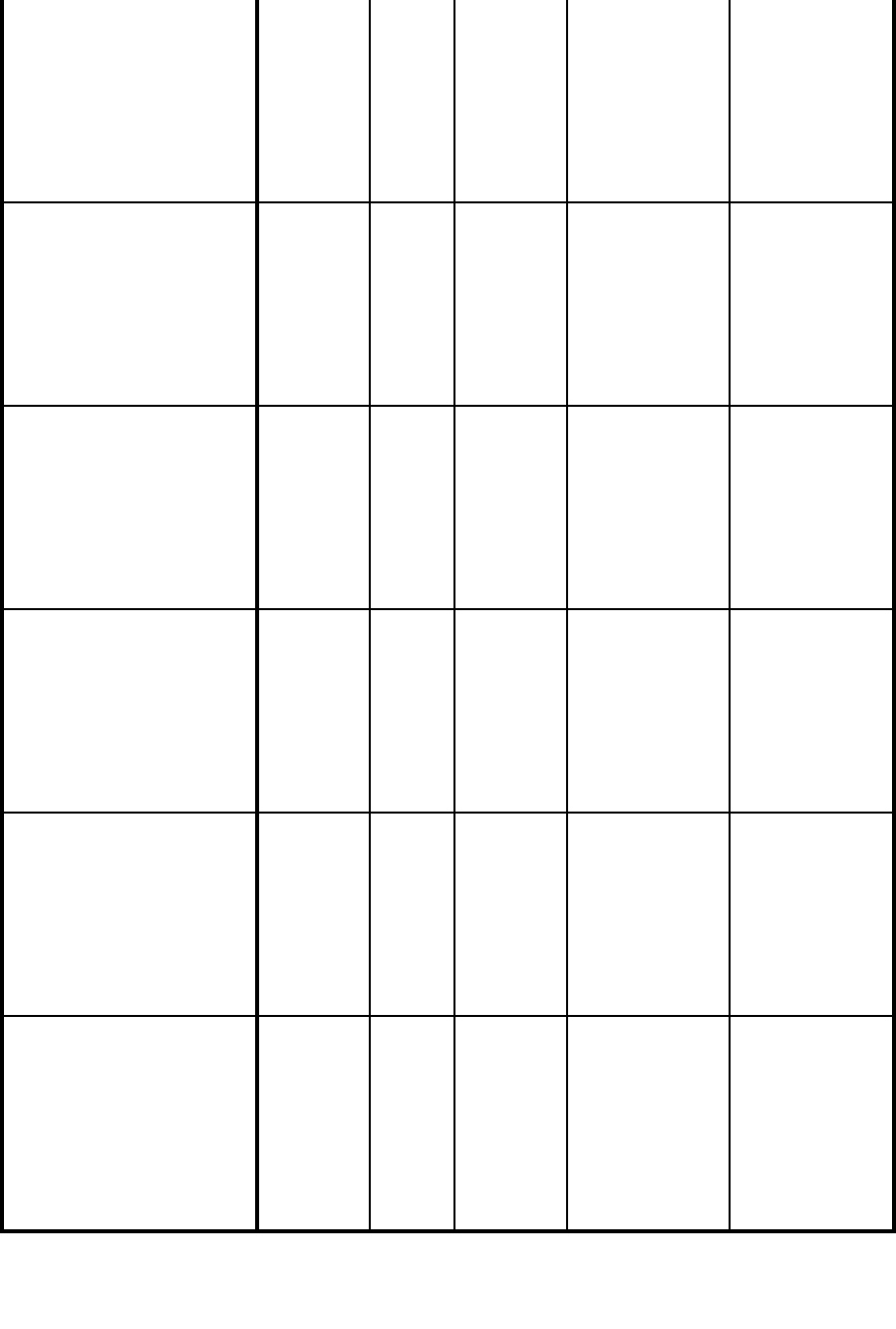

Chart 4.1

Income sources & contribution to income of all charities surveyed: All Incomes

vs. Income < $500k vs. Income > $10m

124

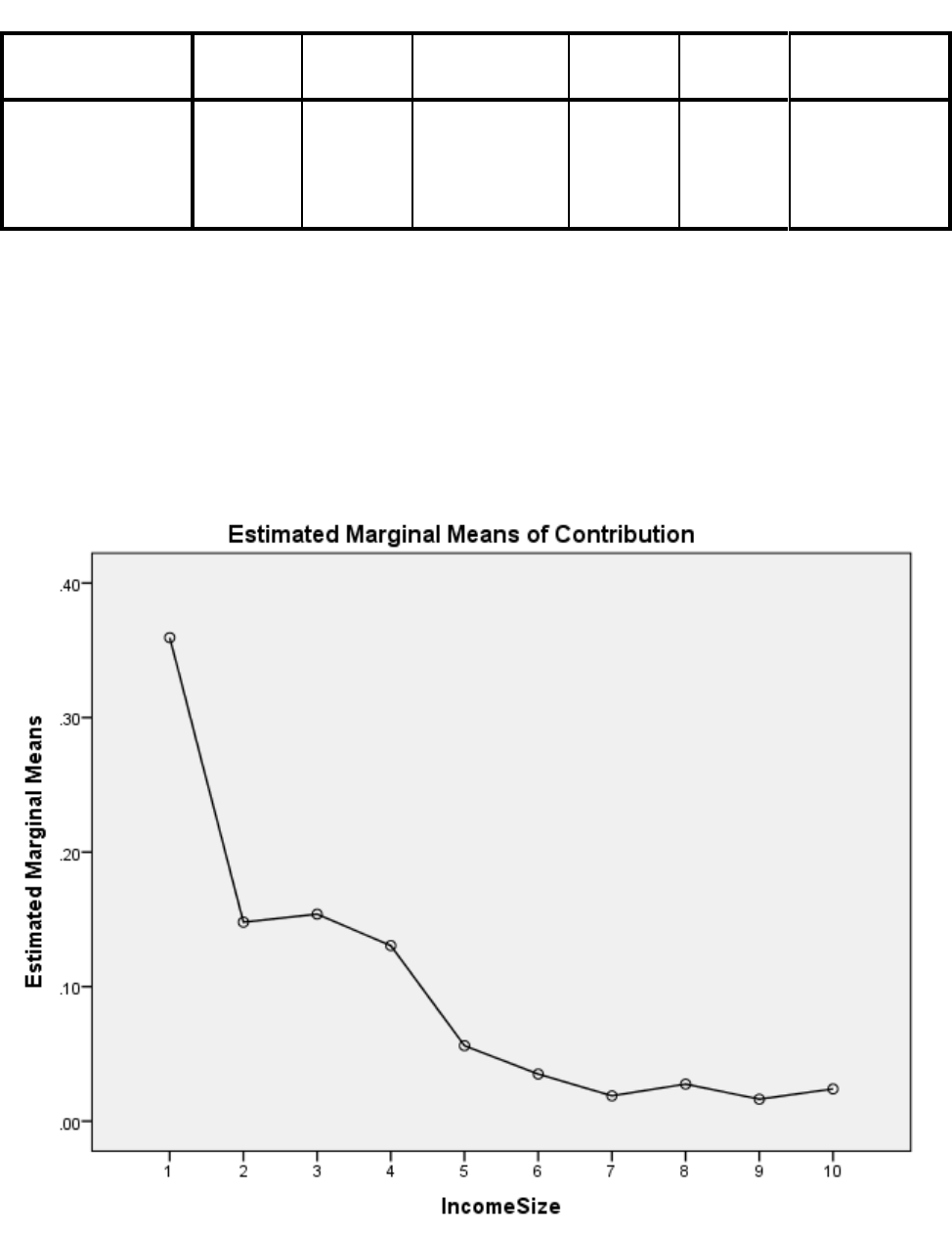

Chart 4.2

Size of grants/donations received & contribution to income of charities

surveyed: All Incomes vs. Income < $500k vs. Income > $10m

127

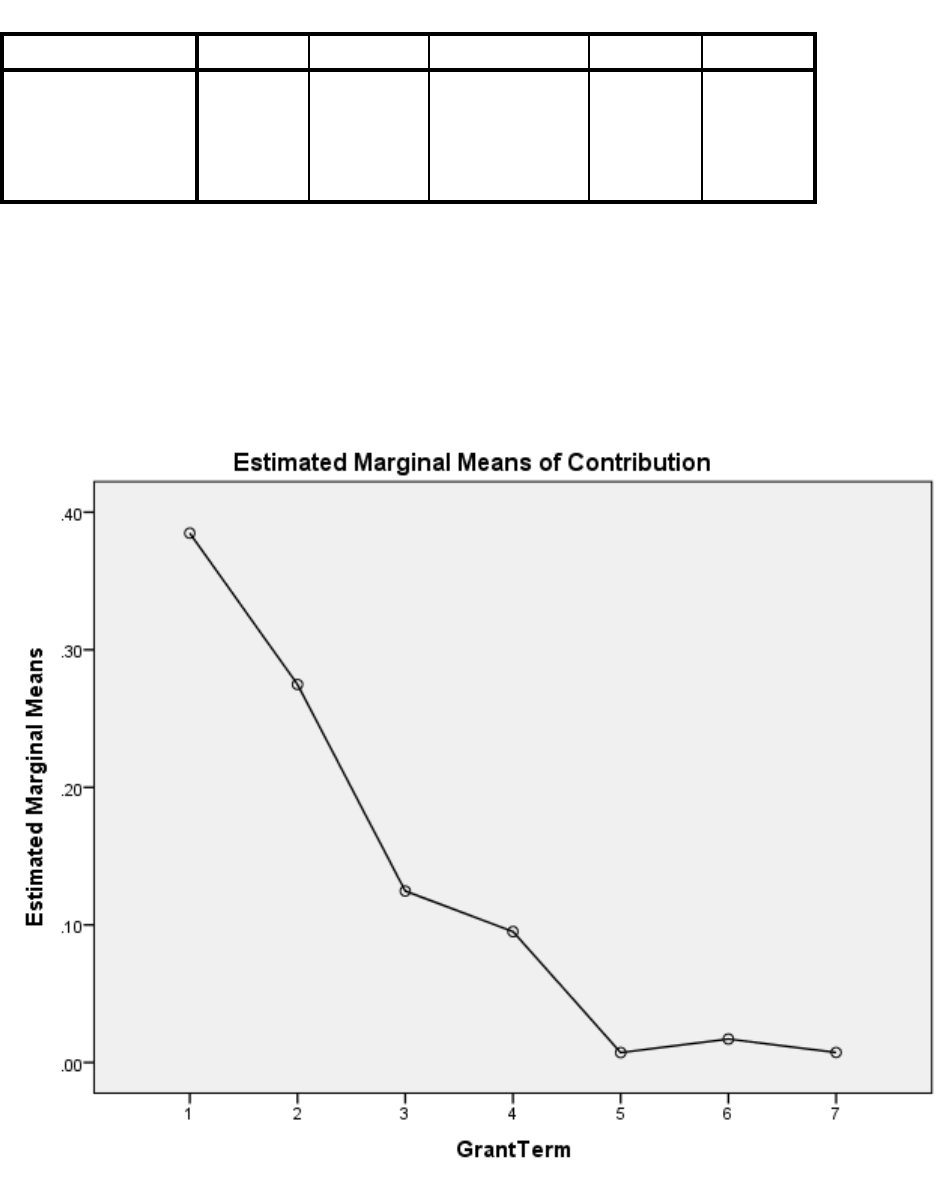

Chart 4.3

Term of grants/donations received & contribution to income of all charities

surveyed: All Incomes vs. Income < $500k vs. Income > $10m

130

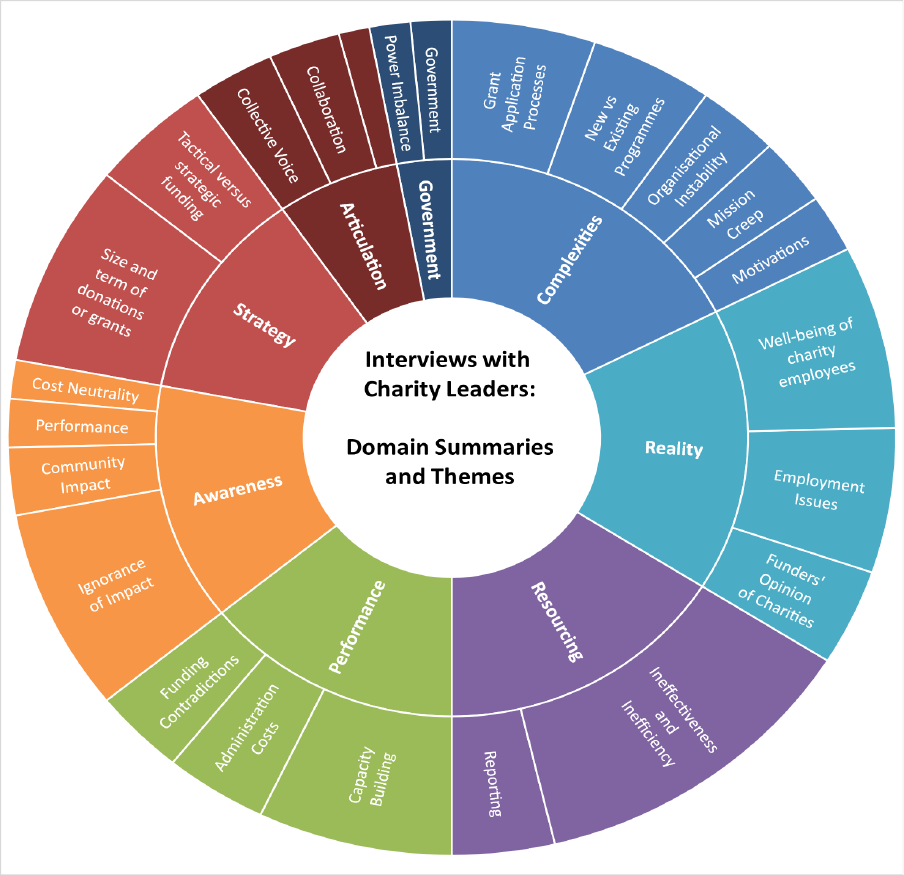

Chart 5.1

Domain Summaries and Themes Charity Leaders

136

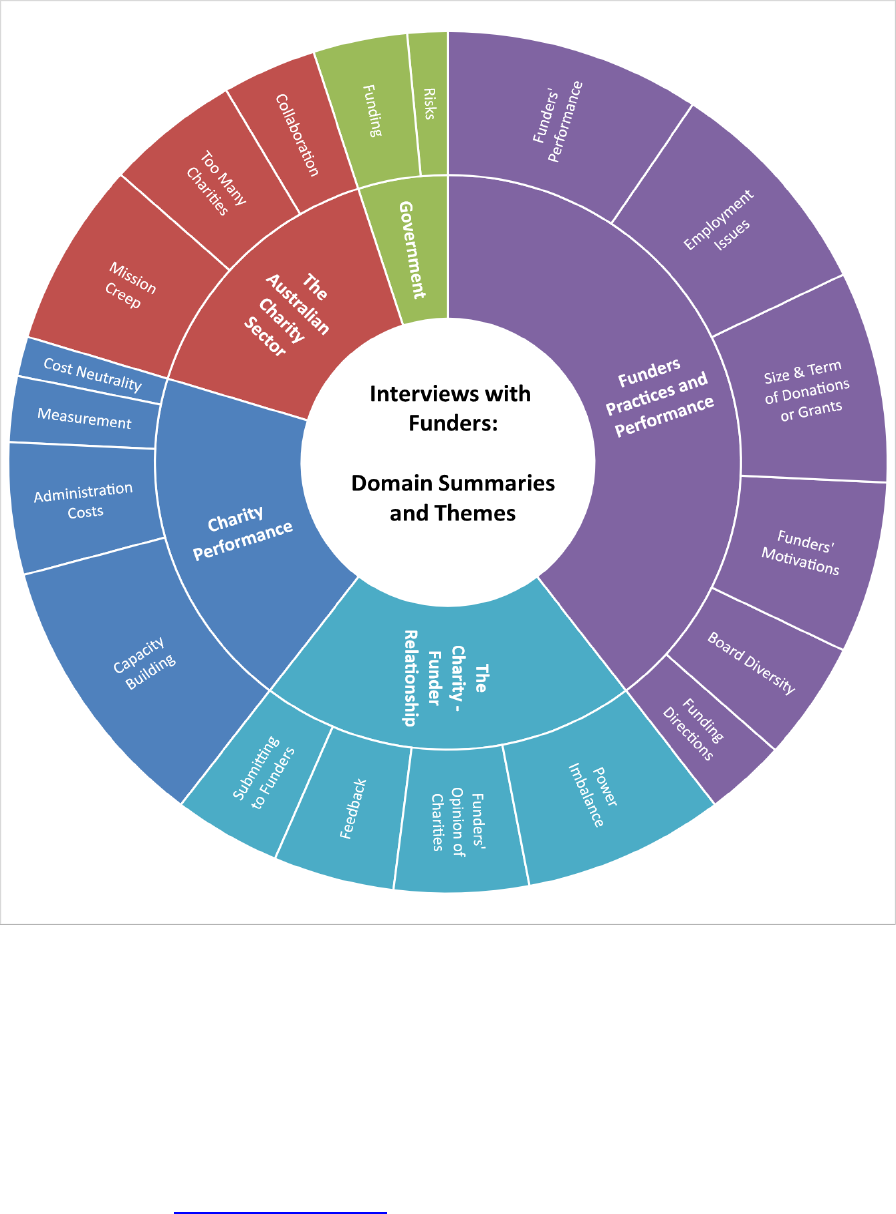

Chart 6.1

Domain Summaries and Themes Funders

167

Chart 7.1

The Funding Iceberg

211

Chart 7.2

Interrelation Influences

212

ix

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for the support of the following:

The participants in the research who volunteered their time and shared their knowledge and

experience of the Australian charity sector and its funders.

My supervisors, Professor Nigel Garrow, Professor David Giles, Professor John Halsey and

Associate Professor Janet Mack who supported, encouraged and provided able counsel throughout

the past several years.

The financial support provided by the Australian Government Research Training Program

Scholarship.

Leaders, faculty and staff of the College of Education, Psychology & Social Work at Flinders

University; Peggy Brooksby, Education Liaison Librarian and Dr Pawel Skuza, Statistical

Consultant, both at Flinders University.

Judith Lydeamore, who provided proof-reading and editing, in accordance with the guidelines laid

out in the university-. All errors contained

in this document remain with the author.

My employers through the duration of this study: Origin Energy, Audi Australia, Panthera Finance

and Big Picture Education.

My family, for their counsel, kindness and patience.

x

Declaration

I certify that this thesis:

1. does not incorporate without acknowledgment any material previously submitted for a

degree or diploma in any university; and

2. to the best of my knowledge and belief, does not contain any material previously published

or written by another person except where due reference is made in the text.

Signed

Thomas W Keenan

Date 19

th

November 2021

1

Chapter 1 - Introduction

1.1 Preamble

My history

I began my direct involvement with charities in 2002 when I commenced employment with

Origin Energy. Prior to that, my knowledge of individual charities and the wider charity

sector was limited. In my role with Origin, I was tasked to develop a hardship program that

would help those energy customers who were experiencing difficulties in paying their energy

bills. It was through this work that I first started my direct interactions with charities,

although the charities I interacted with were limited to those providing financial counselling

support to those in the community who were suffering from financial hardship. These

dealings continued through to 2010 when I moved to the Origin Foundation and adopted the

role of a funder. This change allowed me to build connections across the wider charity sector

and progress my understanding of the sector in the process. Subsequent roles with the Audi

Foundation and the Panthera Foundation have allowed these interactions to expand and

further advance my knowledge of the charity sector.

My standpoint

In summary, I believe the Australian charity sector:

• plays a critical role in supporting the vulnerable and disadvantaged in our societies.

• is less impactful than it might otherwise be due to the work practices forced upon the

organisations within.

• is often treated with indifference by the majority of funders including government.

• consists of passionate, driven, but poorly remunerated employees committed to

individual, family and community progress.

My motivation

Australian charities have been established for the purpose of serving the needs of others.

Many support the at-risk and disadvantaged members of our society in times of need. Others

provide opportunities and encouragement to improve self-worth. Most charities look to

improve our communities by enhancing personal contribution and, as such, charities play a

crucial role in supporting those who are vulnerable and in need (Australian Charities and Not-

3

1.2 Introduction

This section of the chapter introduces the aims of this research and its significance. It

provides a brief overview of the not-for-profit sector and the charities within, identifies the

underlying problem and presents the research questions. In addition, this chapter recognises

the research limitations and describes my personal motivation for undertaking this endeavour.

Finally, this chapter outlines the structure of the thesis and closes with a brief summary.

The research undertaken for this thesis emerged after extensively reflecting on my

experiences as a funder of charities over several years. In particular, my discussions with

charities would frequently turn to focus on what they perceived to be the inefficiencies,

limitations, and damaging impact of the current model of funding employed by most funders.

The concerns and claims made by charity personnel included:

• The vast majority of funders provide small, short-term donations or grants and

securing small, short-term funding from a multitude of funders, rather than just a few,

is a less than effective use of available resource.

• Funders show few similarities in their processes, protocols, and objectives, which

adds further complexities to fund seeking and drives higher administration costs.

• Funders demonstrate a disdain or disregard for supporting capacity or capability

building initiatives, such as employee training and development or upgrading

information technology systems. Subsequently, charities do not include the capacity

and capability building components in their grant applications, which in turn,

exacerbates the lack of targeted funding that would improve the impact these

organisations have on the individuals, families and communities they serve.

• Funders can have other intentions which can be contradictory to their formal

published objectives, as in, funders are likely to want more from their funds than just

community benefit, things such as ongoing recognition and regular employee

engagement, all of which take considerable time and effort and have the effect of

diluting the value of the initial donation or grant.

• Funders do not consider the impact their practices have on charities.

With regards to the abovementioned claim that funders provide mostly small, short-term

funding, this claim cannot be substantiated through existing reporting structures (Australian

Charities and Not-for-Profit Commission, 2020e; Australian Federal Government, 2020c;

4

SmartyGrants, 2020), which are not specific enough to allow a detailed analysis of the size

and term of the donations or grants on offer. Nor can existing reporting confirm that this

model of f. There is also a dearth of

information available that allows evaluation of funders and their impact. As such, claims of a

disdain or disregard for supporting capacity building initiatives, contradictory objectives, and

a lack of consideration of impact cannot readily be substantiated.

However, a recent funding initiative by the Macquarie Group Foundation did afford a source

of support and some insights about the concerns and claims of charities. Put another way, it is

an informing albeit minor case study that provides important contextual elements for this

research.

The Macquarie Group Foundation is the philanthropic arm of Macquarie Group. It provides

support to several hundred charities annually both financially and through volunteering

(Macquarie Group Foundation, 2020a). As part of the Macquari

th

anniversary

celebrations, the Macquarie Group Foundation announced it would be launching its 50

th

Anniversary Awards and distributing $50 million to just five charities over a five-year period

(Macquarie Group Foundation, 2020c). The objectives of the awards were as follows:

• To build on an eligible organisation’s ability to address an area of social need.

• To encourage eligible organisations to be bold in their thinking about how to address social

needs to support excellence in the implementation of these bold ideas.

• To publicly promote the selected organisations’ work and inspire continuing best practice

within the social sector. (Macquarie Group

Foundation, 2020c, p. 1)

The project offered the successful charities $2 million a year for five years to support

innovative ways of improving their ability to deliver services. However, while the Macquarie

initiative provided the chance for a substantial payoff for the successful applicants, a $10

million grant application is not something that is written in a few hours, especially in a

competitive environment. Applicants would have needed to invest significant resources in

putting such an application together. While it is not possible to know exactly what resources

charities devoted to their initial applications, it is not unreasonable to assume that an initial

meeting would occur to decide if an application should be submitted. If the decision were

made to progress, further meetings would then be scheduled to decide what the pitch would

5

be and then how the application should be constructed. Several re-writes would occur, all of

which would have to be reviewed and approved, and then there would be a final sign-off.

Based on my knowledge of the work required to develop a competitive bid for such a large

amount of funding, a conservative estimate of at least four weeks of organisational resources

that included a diverse range of personnel would be required.

The Macquarie Group Foundation received almost 1000 applications (Macquarie Group

Foundation, 2020c). Using my above

competitive bid, the 1000 applications multiplied by four weeks per application would equal

4000 weeks or around 80 working years of resource, and that amount is just for the charities

that fell at the first hurdle of considerations. It is important to also recognise that the figures

and the overall resource use estimates do not include the resource used by those charities

which considered submitting a grant application but did not.

While I acknowledge that the figures I have used in the foregoing analysis are based on my

employment experiences plus some documented investigations into charity funding practices

(Herbert, Barnett, Clarke, & Graves, 2013; von Hippel & von Hippel, 2015), they signal a

ve

original entrants. For the 60 charities who made it through to the semi-finals, a

comprehensive due diligence process was undertaken by external consultants, and further

regional based judging was undertaken across the Americas, Asia, Australia, Europe, the

Middle East and Africa (Macquarie Group Foundation, 2020c). The twelve finalists chosen

then had to undergo site visits by the Macquarie Group Foundation prior to the selection of

the five winners. Whilst this four-stage selection process may demonstrate how meticulous

the Macquarie Group Foundation was in their approach to allocating $50 million worth of

funding, arguably it would have had quite a resource and emotional impact on the charities

involved, especially those who made it through to the final and then failed. Beyond the

aforementioned estimated cost of 80 years-worth of charity resource, as absorbed by the

majority of unsuccessful applicants, the cost to the Macquarie Group Foundation of

employing external consultants and undertaking site visits across six continents would have

also been significant.

It is also very relevant to the contextual framing for my research to foreground Macquarie

Group Foundation methods of funding because they are revealing in terms of the relational

6

complexities existing between funders and charities, namely:

• Matching staff donations and fundraising

• Providing grants to a community organisation with a Macquarie staff member on its board.

• Donating to a staff-nominated organisation for 10-year and 25-year employee anniversaries.

• Providing financial awards to community organisations recognising outstanding Macquarie

staff contributions.

• Making grants to organisations which meet our grants criteria (a small number of grants

outside of these criteria may also be made at the Foundation’s discretion).

(Macquarie Group Foundation, 2020a, p. 1)

It would appear that if a charity was looking to secure funding from the Macquarie Group

Foundation then it must be willing to comply with the aforementioned conditions regarding

employee participation. These conditions suggest that the Macquarie Group Foundation

would appear to preference charities which could provide appropriate employee participation

activities above charities which may be having greater societal impact but were not able or

willing to provide such activities. They also suggest that the Macquarie Group Foundation

approach to funding may, in practice, compromise the stability of existing charity structures

in order successfully achieve its own objectives. In turn, both seem to contradict one of the

stated funding principles, “…we want to achieve the most significant social impact possible…”

(Macquarie Group Foundation, 2020b, p. 1).

As stated at the commencement of this chapter, in my experience, charities often claim that

funders can have objectives which contradict the ones they formally publish. In this instance

the were all published. However, they were

internally contradictory which in turn gave rise to an ambiguity of interpretation and, as a

consequence, opens a range of problematics including the influence and power dynamics in

funding relationships.

From verifying the current models of funding, to assessing the impact these models may be

having on the performance of charities, to exploring the behaviours and motivations of

funders, all these issues were ripe and ready for the in-depth investigation that was

undertaken.

7

1.3 Framing and scope of the research

My relational experiences with charities drove my examination of the existing literature

regarding the models of charity funding that were being employed and their effects. My

experiences also highlighted there was a significant gap in the literature linking how funders

fund and how these practices affect the organisational effectiveness and efficiency of

charities. There is also a literature gap regarding the nature of the relationship between

funders and charities about the impact this relationship has on the effectiveness and

efficiency of charities and the effect on employees within the charity sector. This research

investigates whether charities could improve the impact they have across the communities,

families and the individuals they serve, if funders were to adopt a more nuanced and

relational model of funding, and one which better aligned the objectives of charities with the

funders who support them.

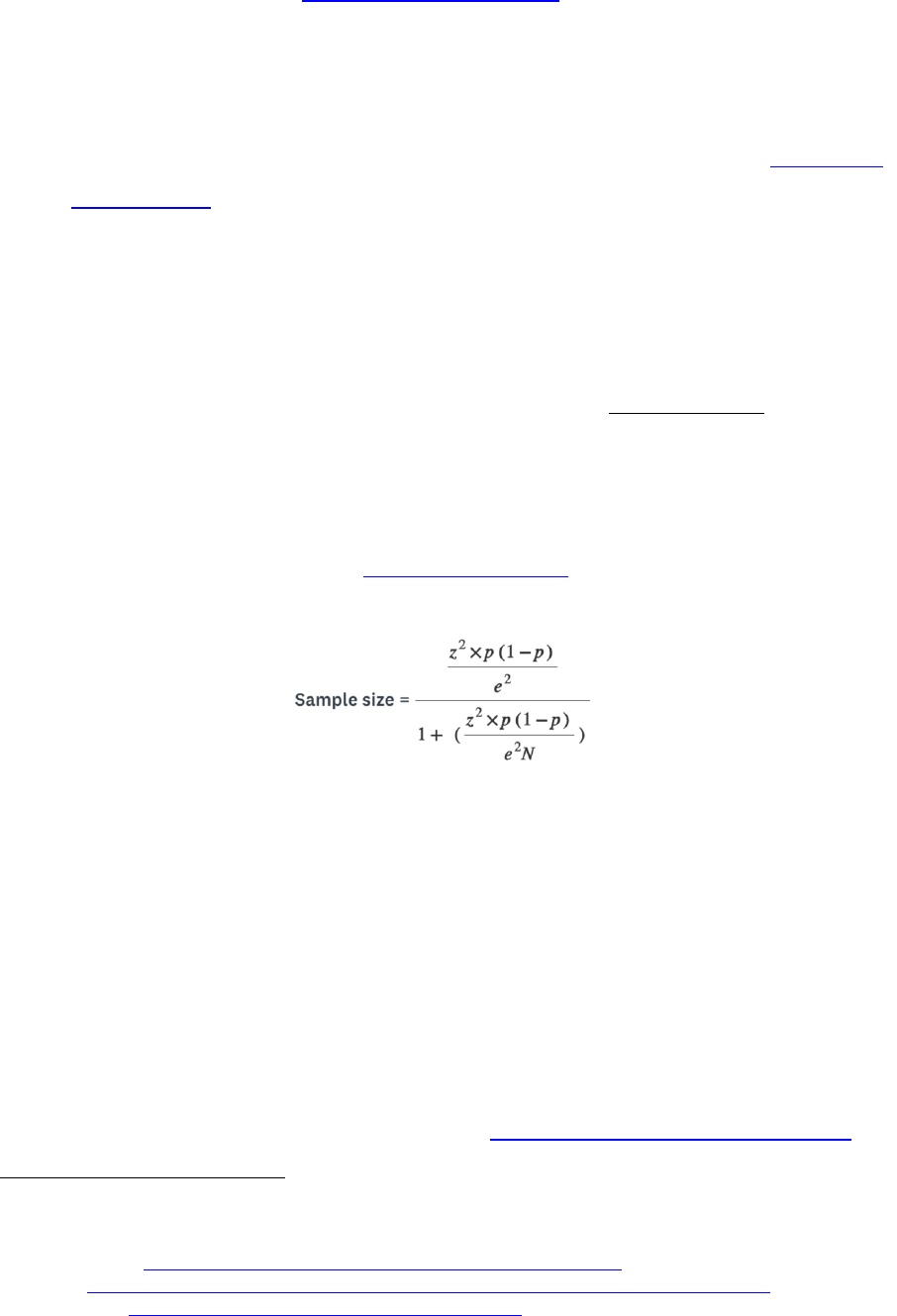

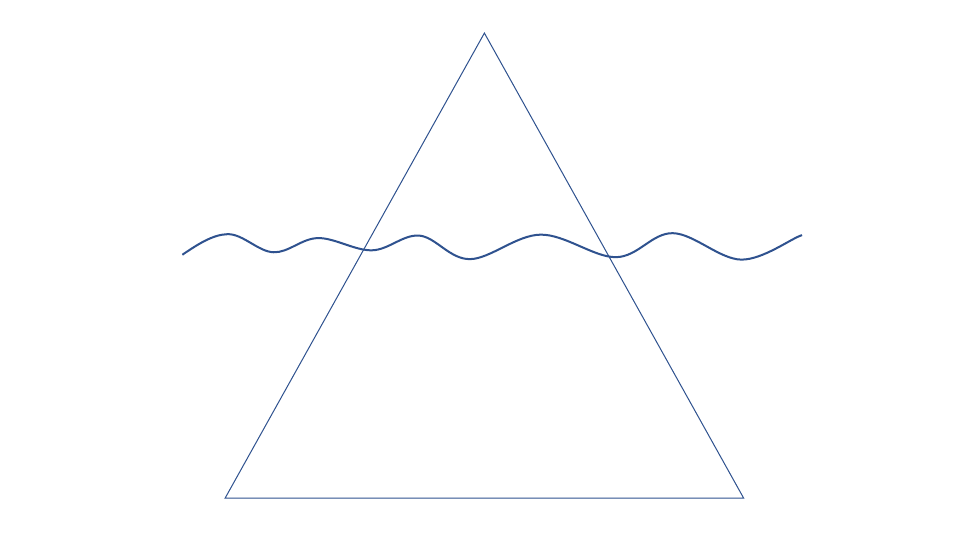

The scope of this research is illustrated in Chart 1.1, which shows four primary components

and the inter-relationships existing between these components. The overlapping rings in this

chart help visualise the importance of collaboration for organisational effectiveness and

efficiency.

Chart 1.1 Scope of the research

8

This research was located primarily in Australia although some exploration and investigation

was undertaken in the U.K. and the U.S.A due to their similarities in the history and practices

of charities and funders.

9

1.4 Research questions

The following questions guided this research:

Main question:

• Is the organisational effectiveness and efficiency of Australian charities impacted by

how they are funded?

Sub questions:

• How does the funding of charities currently occur?

• What is the nature of the relationship between charities and their funders?

• What are the motivations of funders?

10

1.5 Definitions

The primary components of this research were charities, funders, the charity/funder

relationship, funding models and the organisational effectiveness and efficiency of charities.

Definitions of each were used as follows:

1.5.1 Charities

As defined by the Charity Act 2013 (Australian Federal Government, 2013), a charity is:

• a not-for-profit entity.

• having only charitable purposes that are for the public benefit.

• not having a disqualifying purpose.

• not being an individual, a political party or a government entity.

An organisation that is endorsed as a charity by the Australian Charities and Not-for-Profit

Commission under the Charity Act can attract certain monetary benefits, such as income tax

exemptions, General Services Tax (GST) concessions and the ability to receive tax deductible

donations or grants (Australian Tax Office, 2020e). However, and due to the caveat of

having only charitable purposes that are for the public benefitcharity funders such as

private and public ancillary funds or philanthropic organisations (Australian Charities and

Not-for-Profit Commission, 2020f) can also be endorsed as charities. For the purposes of this

research, charities were defined as organisations who are endorsed as charities and who

undertake the actual delivery of charitable and social services, such as advancing education,

relieving poverty or providing health support.

1.5.2 Funders and motivation

A funder is defined as a person or an organisation that provides money for a particular

purpose (Cambridge Dictionary, 2021b; Oxford Dictionary, 2021b). For the purposes of this

research funders were defined as those individuals or organisations that provided funds

(donations or grants) to charities. Funding is defined as the act of providing money for a

particular purpose. Funders practices and behaviour will are influenced by their motivations,

which can in turn be defined as the reason why something is done or why someone behaves

in a particular manner (Cambridge Dictionary, 2021d; Oxford Dictionary, 2021a). For the

purposes of this research, motivation was defined as the impetus

11

1.5.3 The charity/funder relationship

A relationship is defined as the manner in which groups or people regard and behave towards

one another (Cambridge Dictionary, 2021e; Oxford Dictionary, 2021d). For the purposes of

this research, the relationship between charities and funders was explored and considered,

taking into account such aspects as equity, impact, motivations and outcomes.

1.5.4 Funding models

A model is defined as a particular design of a system or a procedure (Cambridge Dictionary,

2021c; Oxford Dictionary, 2021c). For the purposes of this research a funding model was

viewed as the system or procedure employed by funders to allocate their funding.

1.5.5 Organisational effectiveness and efficiency

Organisational effectiveness can be defined as how well an organisation performs activities

similar to a comparable or rival organisation (Michael E. Porter, 1996). It is concerned with

improving performance (Hill, 2012) and, as such, unproductive processes need to be

identified and addressed (Russell & Taylor, 2005). In the commercial world, this could be the

ability to produce products, similar in quality to those of a competitor, but in a faster way.

Effectiveness concerns the performance of all aspects of an organisation and includes such

items as employee reward and recognition, the quality and quantity of products produced,

automation of tasks and the exploitation of information technology (Adan, Bekkers, Dellaert,

Jeunet, & Vissers, 2009; Gomes, Yasin, & Yasin, 2010). Organisational effectiveness

represents the internal drivers for organisations (Gantz, 2013) and it is believed that by

improving organisational effectiveness an organisation will perform better (Michael E Porter,

1996; Santa, Hyland, & Ferrer, 2014). Organisational efficiency differs from organisational

effectiveness in that it is concerned with how cost-effective an organisation is at delivering its

products or services (Ostroff & Schmitt, 1993). An organisation is successful when the use of

resources is both effective and efficient (Osbert-Pociecha, Dudycz, & Brycz, 2016).

A real-world example of how organisational effectiveness and organisational efficiency vary

can be provided by comparing healthcare performance across differing countries. According

to data available from the World Bank (World Bank, 2020), in 2017 the United States of

America had a per capita health expenditure of US$10,246, with an average life expectancy

of 78.5 years. Switzerland had the next largest expenditure at US$8,217 and a life expectancy

of 83.6 years. Norway was third in expenditure at US$6,518 and a life expectancy of 82.6

12

years. This would indicate that healthcare in both Switzerland and Norway is more efficient

(less per capita cost) and more effective (higher life expectancy) than in the United States of

America; it would also suggest that whilst healthcare in Switzerland is more effective than in

Norway, it is less efficient (lo Storto & Goncharuk, 2017).

13

1.6 Background

The Australian charity and not-for-profit sectors

To undertake this research in a rigorous manner and better understand its possible impact, it

was important to have a clear dimensional sense of the not-for-profit sector and the charities

within that sector. This section provides an overview of both the Australian not-for-profit

sector and the charities within it.

In 2014 there were around 600,000 not-for-profit organisations in Australia, most of which

were small and relied on contributions of members and other supporters to survive

(McGregor-Lowndes, 2014). The not-for-profit-sector accounted for around 4% of

c Product (GDP) for 201213, with a value of $57.7 billion, up

from $34.6 billion for 200607 (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2015). From 2000 through to

2013, the GDP contribution of the sector had an annual growth rate of over 8%, well above

that of other Australian industry sectors (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2015). There are

many categories under which an Australian organisation can register itself as a not-for-profit,

which can include:

• churches

• cultural societies

• neighbourhood associations

• public museums and libraries

• sports clubs

• schools and universities

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, the not-for-profit sector employed over one

million people through 20122013. Organisations providing social services accounted for

24.9% of these employees, followed by organisations providing education and research

services at 24.5%. 41.4% of employees were classified as permanent full-time, whilst 34.3%

were classified as permanent part-time. 24.3% were classified as being casual employees.

40% of the employing not-for-profit organisations provided sport and physical recreation

services. (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2015). Beyond direct employment, the not-for-

profit sector is also active in recruiting and mobilising volunteers across Australia.

“…the role of volunteers in not-for-profit organisations is essential…through 2012–

14

2013, 3 million volunteers provided over $17 billion worth of unpaid labour...these

volunteers were most likely to be contributing their time to sport, welfare or

community organisations and religion institutions...” (Australian Charities and Not-

for-Profit Commission, 2015, p. 46).

The direct value that not-for-profit organisations add to the economy is measured as Gross

Value Added

1

(GVA). According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, through 20122013,

the not-for-profit sector accounted

which was an increase on the 20062007 contribution of 3.2%. With regard to Gross

Domestic Product, the sector contributed $57.7 billion through 20122013, up from $34.6

billion in 200607 (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2015).

As stated earlier in this chapter, this research is concerned with the Australian organisations

within the wider not-for-profit sector that undertake the actual delivery of charitable and

social services. Examples of such organisations include:

• Camp Quality a charity that helps children deal with their own cancer diagnosis.

• Guide Dogs Australia a charity that delivers essential services to those who are

blind or vision impaired.

• Oxfam a charity that works to relieve and eliminate poverty.

• RUOK? a self-harm prevention charity.

• The Smith Family a charity that helps children get the most benefit from their

education.

Concerning Australian charities within the wider not-for-profit sector, for the 2017/2018

financial year (FY), the Australian Charities and Not-for-profit Commission (ACNC)

provided the following summary of their contribution (Australian Charities and Not-for-Profit

Commission, 2020e):

• $155.4 billion in total revenue

• Over 57,000 registered charities

• $68 billion received in federal, state and local government funding

• $10.5 billion received in donations and bequests

1

economy (Australian Tax Office).

15

• $148.5 billion in total expenses

• Over 1.3 million employees

• 3.7 million volunteers

With regard to total charity revenue, this has been increasing throughout the past several

years Through FY 2012/2013 total charity income was $100 billion (Australian Charities and

Not-for-Profit Commission, 2014). By FY 2014/015 this income had increased to $134.5

billion (Australian Charities and Not-for-Profit Commission, 2015) with the aforementioned

$155.4 billion reached by FY 2017/2018 (Australian Charities and Not-for-Profit

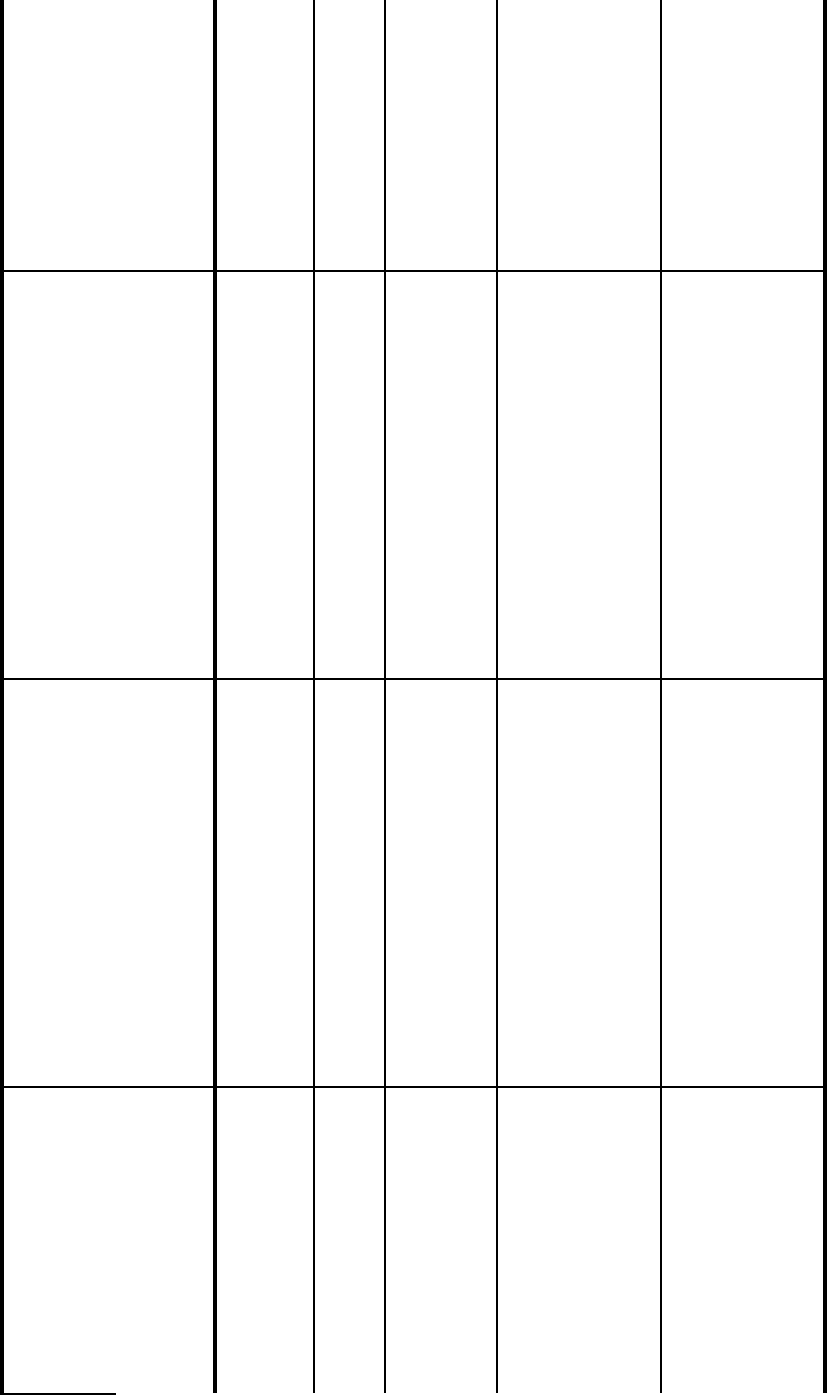

Commission, 2020e). The ACNC also defined the main purpose of Australian charities

(Australian Charities and Not-for-Profit Commission, 2020e) (see Figure 1.2) and the most

common beneficiaries (Australian Charities and Not-for-Profit Commission, 2020e) (see

Figure 1.3). Each of these data sources contributed to an understanding of the impact,

diversity and reach of the sector.

Chart 1.2 Purpose of Australian charities

Chart 1.3 Most common beneficiaries of Australian charities

0% 5% 10% 15% 20% 25% 30% 35%

Culture and Recreation

Development and Housing

Education and Research

Environment

Health

International

Law and Advocacy

Philanthropy and Voluntarism Promotion

Religion

Social Services

16

1.7 Reporting and performance

In order to ascertain what impact current models of funding are having on the organisational

effectiveness and efficiency of charities, a review of existing charity and funding legislation

was undertaken. Reporting obligations for both charities and funders were also explored. An

examination of both legislation and reporting was relevant to establishing the background to

this research, as these create the framework under which both charities and funders currently

operate.

1.7.1 Charities

Throughout the past several decades, there have been various attempts to gain a better

understanding of the impact of the not-for-profit sector and the charities within it. Originating

post-war in the late 1940s, the current System of National Accounts (SNA) is a standard

system of national accounting. Internationally agreed, the SNA looks to provide an

amalgamated, comprehensive system of accounts that allows a transnational comparison of

all significant fiscal activities (United Nations, 2020). The first SNA was published in 1953

-(United

Nations, 1953).

Satellite accounts, provide a method by which certain fields or aspects of economic and

social life can be focused on and by which the SNA can be tailored to meet the contrasting

circumstances and requirements of differing countries. They are intended for precise use,

such as in assessing education progression, tourism activity or monitoring the not-for-profit

sector (Eurostat, 2020).

Published in 2003, the United Nations Non-Profit Institutions Handbook encouraged

countries to produce regular satellite accounts for not-for-profit organisations, including

measurements of the value of volunteer work (United Nations, 2003). The aim was to help

with the task of comparing not-for-profit sector performance across differing countries and

economies. The Handbook offered a standard set of guidelines for identifying charities and

not-for-profits hidden in other economic sectors. Countries were encouraged to separate such

organisations from the sectors to which they had been previously located and combine them

17

into a composite not-for-profit satellite account that included the value of volunteer work

these organisations contributed:

“…the fundamental aim of the present Handbook is to respond to the growing

interest that statisticians, policy makers and social scientists have in organizations

that are neither market firms nor state agencies nor part of the household

sector…such social institutions are variously referred to as “non-profit”,

“voluntary”, “civil society” or “non-governmental” organizations and collectively

as the “third”, “voluntary”, “non-profit” or “independent” sector..” (United

Nations, 2003, p. 3).

While there was a substantial amount of information on Non-Profit Institutions

Satellite Account including funding trends, GDP contribution and volunteer hours in 2015

(Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2015), very little could be deduced from this information

about the performance or impact of the not-for-profit sector or the charities within it. The

issue was meant to be addressed when, in 2009, to fulfil an election promise, the Australian

Federal Government instructed the Productivity Commission to investigate options for

maximising the not-for-profit

economic growth. The Commission was specifically asked to consider how the not-for-profit

sector's contribution to Australian society was measured at that time and whether those

measures could be improved. It was also asked to identify ways to improve the efficiency and

effectiveness of not-for-profit organisations, and to consider options for advancing the

delivery of government-funded services by those not-for-profit organisations (Gillard,

Stephens, & Bowen, 2009).

Within the press release, Senator the Hon Ursula Stephens, Parliamentary Secretary for

Social Inclusion and the Voluntary Sector stated:

“…the study will help improve the way in which the not‑for‑profit sector operates

and make it easier for organisations working in the sector to be effective..” (Gillard

et al., 2009, p. 1)

That quotation was important to this research as it indicated an assumption by the Federal

Government that the not-for-profit sector was not currently performing at optimum levels; an

assumption that was confirmed in the subsequent Productivity Commission Report

Contribution of the Not-for-Profit Sector’, which stated:

18

“…not-for-profits are constrained in improving productivity…areas of most concern

are inadequate governance skills, low uptake of information technology and lack of

capacity in evaluation…” (Productivity Commission, 2010, p. LVIII)

This report included a wide range of observations and findings. It also made a number of

recommendations including:

“…the Australian Government should provide funding for the establishment of a

Centre for Community Service Effectiveness to promote ‘best practice’ approaches

to evaluation…among its roles, the Centre should provide:

a publicly available portal for lodging and accessing evaluations and related

information provided by not-for-profit organisations and government agencies,

guidance for undertaking impact evaluation,

support for ‘meta’ analyses of evaluation results to be undertaken and made publicly

available…” (Productivity Commission, 2010,

p. XLII)

This quote is significant in that it acknowledged a lack of ability to easily evaluate the

performance of the not-for-profit sector and the charities within it. This thesis contributes to

solving this problem by evaluating the impact that the charity/funder relationship and models

of funding have on the organisational effectiveness and efficiency of charities.

Annual Information Statements

The Australian Charities and Not-for-profit Commission (ACNC) was established in 2012

(Australian Charities and Not-for-Profit Commission, 2020a) following recommendations

from various inquiries, reports and reviews including the 2008 Senate Economics Committee

Inquiry into Disclosure Regimes for Charities and Not-for-profits, the 2010 Review into

abovementioned Productivity Commission Report

(Turnour, 2014). In line with Senator Stephens comments, it provided an excellent

opportunity to gain a more rounded understanding of the performance of charities and,

quickly enough, the ACNC proceeded to introduce a number of so-called enhancements and

improvements with regard to charity and not-for-profit reporting obligations or, more

specifically, the requirement to submit an Annual Information Statement (AIS) to the ACNC

(Australian Charities and Not-for-Profit Commission, 2019a). Beyond the AIS, Australian

charities still have few reporting obligations other than basic income versus expenditure

19

statements. There are also some state-based reporting requirements regarding fundraising in

several states including New South Wales (Fair Trading New South Wales, 2020), Victoria

(Consumer Affairs Victoria, 2020) and Western Australia (Department of Mines Industry

Regulation and Safety, 2020), which follow similar formats to those of the AIS. While the

introduction of the ACNC helped lessen the previous state-based reporting burdens and

reduced some of the more onerous regulatory obligations, an opportunity may have been lost

with regard to providing some useful information concerning the performance and impact of

charities. The AIS includes questions about activities, some rudimentary financial

information and other questions in an attempt to better understand the charity sector

(Australian Charities and Not-for-Profit Commission, 2020c). Interestingly, some charities,

such as basic religious charities and non-government schools, have licence to partially

complete the AIS. Charities regulated by the Office of the Registrar of Indigenous

Corporations have no requirement to submit an AIS (Australian Charities and Not-for-Profit

Commission, 2021b). According to the ACNC, there were 57,000 registered charities in 2018

(Australian Charities and Not-for-Profit Commission, 2020b) but only 48,000 of AIS were

analysed for the 2018 Charities Report (Australian Charities and Not-for-Profit Commission,

2020e). A completed AIS does provide a basic overview of each charity, such as annual

income, areas of focus and number of employees. Combined, the AIS data provide a limited

view of the charity sector due to the partial completion rates or non-participation of certain

charities and offer little in regard to charity performance or impact. Additionally, some of the

information derived from the AIS and published by the ACNC (Australian Charities and Not-

for-Profit Commission, 2020d) may be misleading, as a proportion of the total revenue of

charities is in effect being double counted. As stated earlier, funders can also be endorsed as

charities, and as such, funders income will be counted in year when it is received by funders

and counted again as income by the charities who receive it in the form of a grant or

donation.

Other reporting requirements

Beyond the AIS, many charities, who are also registered as businesses, will have the

requirement to submit an end-of-year financial report to the Australian Tax Office, which

may include such items as wages, salaries and other work-related payments (Australian Tax

Office, 2020b). But much like the AIS, this submission provides little information on

performance or impact. A number of charities also produce an annual report. These reports

tend to paint a positive picture of the activities undertaken and results delivered by each

20

charity. They often provide many individual examples of success and recognition is also

given to their funders and supporters (Benevolent Society, 2019; Salvation Army, 2019; The

Smith Family, 2019a). It can be a challenge to find any negative commentary regarding

performance or impact in these reports.

The diversity challenge

Charities are diverse. They operate across most aspects of our communities, providing

services and support that are complicated and distinct. This diversity can further complicate

reporting within the sector. The seemingly simple act of categorising a charity can prove a

challenge:

“…would the Salvation Army be a religious or social services organisation and the Red

Cross an emergency or International Aid organisation…” (McLeod, 2016, p. 6)

This diversity, married to the lack of any practical independent information regarding the

performance or impact of charities, makes it difficult to compare charities:

•

$25AUD (Fred Hollows Foundation, 2019) impactful? And is it more or less

organisationally effective than the Australian Indigenous Mentoring Experience,

which closes the indigenous education gap and generates $9 worth of societal benefits

for each $1 invested in the program? (Australian Indigenous Mentoring Experience,

2019)

• Does the $30,000 cost of training a guide dog to allow a blind or low vision person

the freedom and independence to travel about their community at minimal risk (Guide

Dogs Australia, 2019) contribute more to societal progression than the $52 per month

it costs to provide a vulnerable and disadvantaged child comprehensive educational

support as long as they are at school or Life

program? (The Smith Family, 2019b)

Using reports that are currently available, whether they

end-of-year financial submissions or own annual reports, it is not possible to

determine if a charity is performing well, having an appropriate level of impact or is

organisationally effective or efficient.

21

1.7.2 Funders

Much like available charity reporting, current reporting on funding and funders is limited.

Individual funders have no obligation to disclose any donations or grants made except

through an end-of-financial year taxation return in order to secure a tax deduction. Reporting

from larger and more organised funders generally happens annually and the range of formats

is incredibly diverse, with many differing types of presentation methods used. Only a small

number of funders provide full disclosure of donations and grants made including the

recipient and size (Myer Foundation, 2019; Vincent Fairfax Family Foundation, 2018). Some

funders provide listings of recipients but omit any useful financial information regarding the

grants or donations provided (English Family Foundation, 2020; Gandel Philanthropy, 2020).

Others provide a summary of funding distributed through the reporting period including the

total amount distributed and the total number of recipients; commentaries regarding certain

recipients may be included (Ian Potter Foundation, 2019; Minderoo Foundation, 2019). Some

large funders do not publish their own information, instead it is made public through the

parent companact or sustainability report (Telstra, 2020; Westpac, 2019).

Funders who are registered as businesses have the requirement to submit an end-of-year

financial report to the Australian Tax Office which incorporates an income and expenditure

statement (Australian Tax Office, 2020b). This reporting gives visibility to how much a

funder has distributed and to whom, but only on an individual basis. There is no

straightforward method of aggregating this reporting other than examining each individual

report and combining the distributions. Funders, endorsed as charities, have to complete an

Annual Information Statement (AIS) and submit it to the Australian Charities and Not-for-

profit Commission (ACNC). Analysis of the AIS data could provide a method of

demonstrating the size of donations or grants as distributed to charities, as in who gave what

and to whom, but the AIS dataset, in its current form, provides only a summary of a funders

distributions and is presented as follows:

• grants and donations made for use in Australia

• grants and donations made for use outside Australia

(Australian Charities and Not-for-Profit Commission, 2020c, p. 1)

Information from charities regarding the receiving of donations and grants is equally limited

and presented as follows:

• revenue from government

22

• donations and bequests

• revenue from goods and services

• revenue from investments

• all other revenue

(Australian Charities and Not-for-Profit Commission, 2020d, p. 1)

This information exists only for the cohort of funders who are endorsed as charities. Funders

who are not endorsed as charities do not submit an AIS, although the charities who receive

donations or grants from this cohort report this as income through their own AIS.

Funding mechanisms

Some funders establish ancillary funds through which they then provide their funding. An

ancillary fund is a mechanism which links funders to the charitable organisations that can

receive tax deductible donations as deductible gift recipients (DGR) (Australian Charities and

Not-for-Profit Commission, 2020h). Ancillary funds can also be endorsed as charities and

secure DGR status

2

, which allows donations into these funds to be tax deductible. Ancillary

funds can take many forms, such as a collection of properties, a share portfolio or a pool of

money (Australian Tax Office, 2020d). There are no rules regarding how ancillary funds,

private or public

3

, distribute their funds other than how much of the fund must be distributed

annually. A private ancillary fund must distribute at least 5% or at

least $11,000 during the financial year, whichever amount is greater (Seselja, 2019). Public

ancillary funds have similar requirements and must distribute at least 4% of the

assets or at least $8,800 during the financial year, whichever amount is greater (Australian

Federal Government, 2011).

In summary, ancillary funds provide a tax efficient vehicle for funders regarding their giving.

Once established, donations into an ancillary fund are tax deductible and donations can take

the form of money shares or property (Australian Tax Office, 2020a). Assets within the

ancillary fund are tax exempt and franking credits from shares are refunded. An inheritance

or the sale of a business can often be the motivator for establishing an ancillary fund as it can

2

DGR status Item 1 refers to organisations such as charities, schools and hospitals, which are organisations that

provide charitable services. DGR Status Item 2 refers to ancillary funds, which are set up solely to provide

money or other benefits to DGR Status Item 1 organisations. (Source:

https://abr.business.gov.au/Help/DGR#itaa)

3

Private ancillary funds can not solicit donations from the general public; public ancillary funds can. (Source:

https://www.ato.gov.au/Non-profit/Getting-started/In-detail/Types-of-DGRs/DGR-table/?page=13)

23

aid in the offsetting of a capital gain (Ruffell, 2014). Funders who use ancillary funds are

obligated to report annually. Those who are endorsed as charities with the Australian

Charities and Not-for-Profit Commission submit the aforementioned Annual Information

Statement. Others submit an Ancillary Fund Return to the Australian Tax Office. This return

requires similar information to that of the Annual Information Statement, particularly income,

expenses and expenditure. It therefore mirrors the previously referenced reports and provides

little information on either performance or impact.

Other funders of charities are federal, state and local governments. Through FY 2017/18,

47% of all charity income came from government (Australian Charities and Not-for-Profit

Commission, 2020e).

Federal government funding

Funds distributed by the Australian Federal Government are administered by the Department

of Social Services through the Community Grants Hub (CGH), which facilitates the

application processes and awarding of grants for several federal government departments

including the Department of Education, the Department of Health and the Department of the

Prime Minister and Cabinet (Australian Federal Government, 2020a). Grants distributed

through the CGH are governed by the Commonwealth Grants Rules and Guidelines 2017

(CGRG). A grant under these guidelines is defined as:

“…an arrangement for the provision of financial assistance by the Commonwealth or

on behalf of the Commonwealth:

a. under which relevant money or other Consolidated Revenue Fund money is to be

paid to a grantee other than the Commonwealth; and

b. which is intended to help address one or more of the Australian Government’s

policy outcomes while assisting the grantee achieve its objectives...”

(Australian Federal Government, 2017, p. 6)

Under the CGRG, grants are provided for many differing activities including capacity

building, infrastructure and research but are not used for the procurement of services:

“…for the purposes of the CGRG, the following financial arrangements are taken not

to be grants:

a. the acquisition of goods and services by a relevant entity, for its own use, including the

acquisition of goods and services on behalf of another relevant entity or a third party.

These arrangements are covered by the Commonwealth Procurement Rules…”

(Australian Federal Government, 2017, p. 7)

24

The previous two quotations are important to this research as they define what is and is not a

grant. This research is concerned with grants and donations; it is not concerned with the

procurement of services.

Procurement of services occurs when an organisation acquires services to meet a need of that

organisation (Cordell & Thompson, 2019; Mangla & Luthra, 2019). A health care provider

purchasing physiotherapy services or a supermarket chain purchasing transport and logistical

services are examples. Procurement of services agreements are usually commercial

arrangements. Over the past few decades, many neo-liberal governments have sought to

extract themselves from the responsibilities for providing social services, instead

relinquishing those responsibilities to charities (Spies-Butcher, 2014; Stewart, 2019; Watts,

2016). As a result, many charities now have procurement of service relationships with

government. A deeper exploration of these relationships is undertaken in Section 2.10.

A grant is an arrangement when an organisation, typically a funder, provides financial

assistance to a charity, which is intended to help address an outcome favourable to the charity

and the funder (Heyman, 2016; Pettey, 2008). Examples include an educational focused

funder supporting a reading programme or environmentally focussed funder

supporting . Reporting on the grants distributed by the

Australian Federal Government is provided through the Grant Connect website. For the FY

2018/19 30, 820 grants were awarded with a combined value of over $18.6 billion.

(Australian Federal Government, 2020c).

State government funding

Individual states also distribute grants to charities and tend to follow similar models of

application, award and distribution. The procedures involved in securing a grant and

subsequent reporting of the monies distributed and outcomes achieved in the five of

most populous states is described below.

New South Wales

The Government of New South Wales uses various interfaces to facilitate grant applications

and awards including Service NSW, the My Community Project and Local Community

Services Association (NSW Parliamentary Research Service, 2019). Local governments

25

within New South Wales collaborate with both federal and state to provide grant

opportunities to targeted communities (Local Government NSW, 2020).

Queensland

In Queensland, grant applications and awards are administered through the Queensland

Government Grant Finder Website (Queensland Government, 2020b) with links to local

government grants also provided.

South Australia

The Government of South Australia Government facilitates its grants through its

GRANTassist and GrantsSA websites (Government of South Australia, 2020b), despite both

websites seemingly being focussed on achieving the same outcomes, including community

participation and wellbeing (Department of Human Services, 2020; Government of South

Australia, 2020a).

Victoria

The Victorian Government follows similar legislation to that the Australian Federal

Government in that it clearly defines the definition of a grant through the Victoria Common

Funding Agreement. A grant is defined as a sum of money given to an organisation for a

certain purpose in order to achieve objectives that are consistent with government policy. A

grant is not a donation or a sponsorship agreement nor is it for the procurement of services

(Victoria State Government, 2020c). also facilitated in a similar manner,

being offered through either the main Victorian Government website or that of Business

Victoria (Business Victoria, 2020; Victorian Government, 2020).

Western Australia

Much like other states, the Government of Western Australia uses a web portal to help

potential grantees to locate an appropriate grant (Government of Western Australia, 2020c),

primarily administered by the Department of Communities (Government of Western

Australia, 2020b) and the Department Local Government, Sport and Cultural Industries

(Government of Western Australia, 2020a). With regards to the funding of grants, the use of

Lotterywest statutory body signals a significant difference between

Western Australia and the other states. Lotterywest sells a number of differing types of

lottery tickets through an approved network of newsagents and online applications

(Lotterywest, 2020). Through FY 2018/19, Lotterywest distributed grants to the value of over

26

$281 million to 613 different not-for-profit organisations and local government authorities

(Lotterywest, 2019). Lotterywest reports annually on how much and to whom it distributed

its grants.

Overall, reporting on government distributed grants is complicated, disconnected and sparse.

Due to this lack of available data, a direct comparison cannot be made between

stated amount of $68 billion of government funds distributed through FY 2016/17 and that of

federal, state and territory government reported distributions. A deeper exploration of

funding offered and awarded to charities by federal, state and territory governments is

undertaken in Chapter 2.

1.7.3 Conclusions

Whilst both Australian Federal and the Victorian State Governments define what is and what

is not a grant, some other states do not afford such rigour to their protocols. For a charity

working nationally, it may be that the differences between a grant and the procurement of

services could easily become blurred.

Much like charities, there is little available reporting on funders and their impact. Where

reporting does exist, a picture of who gave what to whom can be painted. However existing

reporting does little to illuminate or demonstrate the efficacy of funders. There is no easily

accessible method of assessing whether funders are having a positive or a negative impact on

the organisational effectiveness or efficiency of the charities they support.

27

1.8 Limitations and delimitations

At the commencement of this research, it was deemed prudent to give consideration to factors

and influences that may have a bearing on its progress (the limitations), over which I might

have had little control. It was also prudent to set boundaries around the research (the

delimitations), stating what it would not do.

Limitations

The limitations for this research may have included:

• The health of myself, my family and other participants

• The willingness of both charities and funders to participate in this research

• Access to participants, which may be affected geography, weather or a lack of

technology

• The reluctance of participants to openly share their experiences.

Delimitations

This research would not:

• Duplicate current research into charities, funders and funding

• Assess the organisational effectiveness or efficiency of charities.

28

1.9 The significance of the study

The central tenet of this thesis is that relationship dynamics within and between different

organisations, in this case charities and funders, are considerable in influencing and indeed

determining the social impact of their joint endeavours. This thesis explores power imbalance

(Essabbar, Zrikem, & Zolghadri, 2016; Hendrickson, 2003) and relationships (AbouAssi &

Bies, 2018; Giles, 2008) as the central theoretical components underpinning the research,

with accompanying

of the relationship between the two parties, and what action may be required to address

matters arising.

The work being undertaken by the charity sector and its funders is of vital importance to the

Australian people. This thesis advances knowledge regarding the working of the charity

sector, its funders and the challenges faced, in order to enhance their valuable contribution to

society.

This study is significant in that any improvements to efficiency, effectiveness or funding of

charities are likely to have extensive and comprehensive benefits for the whole of the

Australian community. It will also have relevance across a number of other sectors including

government, philanthropy and other major funders. Due to the similarities with charity

sectors in other countries, this study also has the potential to have a positive international

impact.

29

1.10 Structure

The thesis comprises eight chapters. A description of each chapter follows:

Chapter 1 provides an introduction to the research.

Chapter 2 reviews Australian and international literature to inform this research

within the wider body of knowledge and information regarding the effectiveness and

efficiency charities, how charities are currently funded, the nature of the

charity/funder relationship and the motivations of funders.

Chapter 3 describes how the research question was investigated and what activities

were undertaken in pursuit of this goal, including the methodology and the theoretical

framework used.

Chapter 4 presents and discusses the results of the financial survey undertaken.

Chapter 5 presents and discusses the results from the interviews with charity leaders.

Chapter 6 presents and discusses the results from the interviews with funders.

Chapter 7 compares and discusses the results presented in Chapters 4, 5 and 6.

Chapter 8 presents the conclusions from this study, provides possible solutions to and

recommendations about the issues at hand, and identifies further areas of research.

30

1.11 Summary

This chapter has presented the scope of this research and its rationale. The research questions

articulate the need that exists to better understand how charities are currently funded, what

are the effects of this model of funding and is there an opportunity for improvement. The

significance of this research is that it has the potential to benefit much of Australia

and beyond. It will also provide a voice for the charity sector, a sector that has historically

been reluctant to be either critical or heard.

31

Chapter 2 Literature Review

2.1 Introduction

The aim of this thesis was to explore whether the model used to fund charities has any

potential to also improve the organisational effectiveness and efficiency of charities. This

chapter reviews Australian and international literature in the following four fields:

• Current models of charity funding.

• Organisational effectiveness and efficiency of charities.

• Motivations of funders.

• The charity/funder relationship.

The Literature Review sets the scene for the thesis by presenting some of the available

knowledge which is relevant for this study and in particular for answering the research

questions, explaining the problem that this research is addressing, and identifying the gap in

existing knowledge and practice. This chapter also considers

how this role emerged through a review of literature on charity history, charity legislation and

the welfare state.

32

2.2 Relationships within and between organisations

In the private sector, a lack of alignment of the goals of an organisation and its managers can

be a critical relationship issue; Agency Theory (M. C. Jensen & Meckling, 1976) is

concerned with this phenomenon. In the charity sector, the key relationship issue is between

two different types of organisations, namely the charities and the funders, and can be a

function of a potential power imbalance (Essabbar et al., 2016) between the two

organisations. The relationship between charities and

, according to Social Exchange Theory, is the basis of almost all relationships

(Homans, 1958).

Coule (2015) explored the relationship between governance and accountability (Coule, 2015),

commenting on governance theories such as Agency Theory (M. C. Jensen & Meckling,

1976) and Stewardship Theory (Donaldson & Davis, 1991). Other theories which have

relevance to this thesis include Managerial Enrichment Theory (Shleifer & Vishny, 1989), the

premise of which is that managers have an incentive to increase their value to a shareholder

even if it is at the expense of accruing value to shareholders as a whole; and Upper Echelon

Theory (Hambrick & Mason, 1984) in which the proposition “…is that organisational outcomes

– both strategies and effectiveness – are viewed as reflections of the values and cognitive bases of

powerful actors in the organisation…” (Hambrick & Mason, 1984, p. 193) . These theories help

demonstrate the behavioural complexities within organisations as well as between

organisations.

33

2.3 The history of charities and charitable giving

affection or esteem (Lichtenberg, 2009). The Cambridge Dictionary defines charity as: a

system of giving money, food, or help free to those who are in need because they are ill, poor,

or have no home, or any organization that has the purpose of providing money or helping in

(Cambridge Dictionary, 2021a). The Oxford Dictionary provides several wider

or money given to thos

(Oxford University, 2021). Other synonyms can

include aid, altruism, benevolence, giving, humanitarianism, and philanthropy.

Beyond the challenges of securing an understandable and widely accepted definition, there is

much evidence that the broad concept of charity, charitable giving and philanthropy has been

in existence for many, many centuries.

-1200 BC), Manusmriti (c.

1250-1000 BC) and Chandogya Upanishad (c. 800-600 BC) texts (Hinduwebsite, 2020; Islam

& Hinduism, 2020; Sanskiriti, 2014; Sugirtharajah, 2001). The ancient Greeks made claim to

introducing the term p

is believed the term was coined 2500 years ago with its use in the myth Prometheus Bound

(Bond, 2011). Prometheus, who was punished by Zeus for stealing fire from the Gods, argued

(Philanthrocapitalism, 2020). In

ancient Egypt, the Book of the Dead stated that passage to the afterlife was dependent on a

lifetime of benevolence toward the suffering (Science Encyclopedia, 2020). Chinese culture

has a long-established focus on compassion toward others. In ancient China, many proverbs

exist, such as:

(Zhen,

2012). A 2,000 year old proverb

(Chan, 2015). Many Chinese historical

figures hold a special place in history due to their charitable deeds, such as Tao Yuanming of

the Jin Dynasty (365 427), Zi Rudao of the Yuan Dynasty (12791368) and Yang Zhu of

the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) (Zhizhen, 2010).

34

Moving forward in time, London

monk Rahere and has provided free health care to the poor ever since (Barts Heritage, 2020)

and Bethlem Royal Hospital was established in 1247 to provide shelter and care for the

homeless (Science Museum, 2020). Also in London, St Thomas' Hospital was founded in the

early 12th century (British History Online, 2020). In more modern times, as the Ottoman

Empire expanded the Islamic practice of waqf endowment of property for religious or

charitable purposes gained favour. Roxelana, the wife of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent

(1494-1566), used waqf to establish the Haseki Sultan Imaret charitable complex in

Jerusalem, supporting the vulnerable and disadvantaged. By the 18

th

century corruption was

widespread and the complex was no longer financially viable (Boncuk, 2004; Celik, 2015).

In the mid-17

th

century in America, two significantly important acts of educational

philanthropy occurred. In 1638, John Harvard, an English minister, bequeathed his library of

400 books and half of his estate to the local college, later to be called Harvard. He was the

(Harvard University, 2020). A few years later in 1643, the very first

fundraising event in America was organised by Harvard University to complement a £100

scholarship endowment provided by Lady Anne Radcliffe Mowlson, an English

businesswoman. This philanthropic concept quickly spread to other educational institutions

including Yale and Princeton (Fuller, 2014).

Founded in Portugal in the late 15

th

century, the Irmandade da Misericordia (Brotherhood of

Mercy) expanded its footprint into South America and in 1739 used philanthropy to establish

one of the first examples of a women and children institution in Brazil. Shelter and

educational opportunities were provided, which set a new standard for charity work (K. D.

McCarthy, 2001; Schwatrz, 2010).

During the 19th Century in England, a number of charitable organisations were established

with a view to addressing the appalling living conditions found in the city slums. These

initiatives were known as Model Dwelling Companies and were privately owned entities such

as: the Metropolitan Association for Improving Dwellings of the Industrious Classes, the

Peabody Trust and the Artisans, Labourers and General Dwellings Company (Dennis, 1989).

These organisations attempted to improve the housing conditions of the working classes and

also earn a competitive rate of return on any investment. This act of philanthropy, married to

the intention to gain a return on capital invested, (Tarn,

35

1974). Also in England and through the mid to late nineteenth century, Octavia Hill, a social

reformer, and John Ruskin, an art critic, social thinker and philanthropist, further developed

unskilled labourers

(Walker, 2006). Hill also had a belief that her tenants would benefit from having easy access

to the country and other open spaces, and she founded The National Trust (Boyd, 1982;

Craik, 2011). In his book, Unto This Last and Other Essays on Political Economy, Ruskin

advocated that the state should guarantee the standards of social service, and encouraged such

initiatives as youth-training schemes leading to employment, and pensions for the elderly and

vulnerable (Ruskin, 1862). Many of his concepts would be later incorporated into what we

now know as the welfare state.

At the same time in the United States of America, Andrew Carnegie was proposing a new

method of dealing with wealth inequality beyond the traditional practices of patrimony

(handing wealth down to heirs) and bequests to the state for public benefit. He contended that

surplus wealth was put to best use when prudently managed by those who had accumulated

the wealth (Carnegie, 1901). By the time of his death in 1919, Carnegie had donated

US$350,000,000, establishing such institutions as: Carnegie Mellon University, the Carnegie

Institute of Science, and the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. He also

established over 2,500 libraries worldwide (Carnegie Corporation of New York, 2020).

Turning to Australia, the New South Wales Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge and

Benevolence was founded in 1813 by Edward Smith Hall. Hall migrated from England in

1811 and proved to be an influential figure in the colony. He was a banker, newspaper editor

and grazier (Pike, 1966)

Benevolent Society of NSW, becoming non-religious (Benevolent Society, 2020). The

establishment in Australia of many other charities followed, including The Saint Vincent de

Paul Society in 1854, Mission Australia in 1859 and The Salvation Army in 1880.

Tthe past, where benevolent practices were intertwined

into both community and belief structures. Driven by individuals, these benevolent practices